Intern Tea Potato here with even more water experiments!

Les eaux

The two waters we’ll be experimenting with this week are Crystal Geyser and Onsen Sui 99. Crystal Geyser comes from the United States of America. There are several different springs from where the water is sourced, so it’s important to check the bottle to see specifics. In this case, our Crystal Geyser comes from their Mt. Shasta source. Onsen Sui 99 comes from Tarumizu Onsen in Kagoshima Prefecture, an incredibly alkaline water with a pH of 9.9.

Calcium!

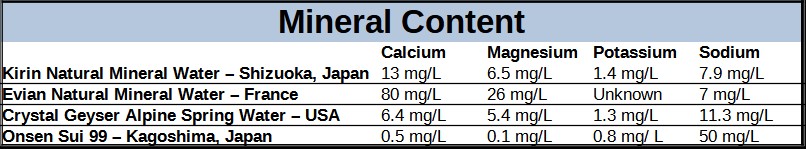

What causes the different flavors in water? It primarily comes down to the minerals. Water is not just H20, but it is also chock full of different minerals. A term you’ll see often on water is TDS, or total dissolved solids. TDS is a measure of the amount of solids in water. However, what those solids are is incredibly important. The four main minerals that you’ll see in water are sodium, calcium, magnesium, and potassium. These minerals are so important, depending on your country, your bottled water may actually list the amount, Japan does (Sometimes they’ll list a salt equivalency instead of a sodium value but that can be math’d into a sodium amount). These four minerals play a big part in the hardness of the water and the alkalinity of the water.

Today, we’ll talk a little about calcium. You’ll see a lot of bottled waters advertising their calcium levels. Calcium influences the hardness of the water and will create a smoother water. But smoother water can come at a price by actually smoothing out the flavor of tea as well. If you have a sharp, biting tea, this may be preferable, but many teas that are more gentle can have all their flavor crushed.

Calcium does something really interesting to tea. Increasing the amount of calcium in water will increase how fast the tea infuses. However, the total amount of…bits? that can be extracted from the tea leaves is reduced. Visually, this can be seen. If one makes a tea the exact same way with two waters, with the only difference being one water has more calcium, the tea with more calcium will be darker and more yellow. (Yin, 2014) If only there was a way to conduct that experiment ourselves…

The Experiment

I brewed Sencha of Brightness twice with Wazuka well water. The first time, there was nothing added to the water. The second time, I added 48 mg/L of calcium chloride to the water. Why do I have calcium chloride on hand?

The tea on the left was made with the regular well water. The one on the right, with the added calcium chloride. As you can see, the tea liquor is darker and more yellow in the calcium chloride water.

Of course, calcium is not the only reason for teas to be darker and yellow, but it is a major factor influencing the flavor and color. And if you flip back to the first experiment with Evian and Kirin, all the teas (matcha notwithstanding) are darker with Evian. These minerals are often listed on water bottles, so we might as well be paying attention to them as well.

And now, on to the main event! Sencha of the Earth, Amber Houjicha, Pine Needle Wakoucha, and Gokou Matcha brewed with Crystal Geyser and Onsen Sui 99.

Sencha de la terre

Sencha of the Earth brews up with a long rich umami flavour, and while there is some bitterness, it’s a pleasant bitterness that doesn’t linger on the sides of the tongue, such as Evian did last time. On top of the umami there are strong dandelion green aromatics that are close to being floral, but not. Metallic notes show briefly, as does a rock candy sweetness.

Onsen Sui 99 has a touch of grapefruit bitterness surrounded by light floral aromatics. There is next to no umami in the brew. One of it’s most noticeable characteristic was a salivating astringency. While in some cases, astringency is not a positive, in this case, I’m a fan. Unfortunately, all of the flavours appear only briefly, before disappearing quickly. All that’s left is the astringency.

Figure 202. Sencha of the Earth brewed with Onsen Sui 99 on the left, on the right brewed with Crystal Geyser.

Amber Houjicha

Amber Houjicha and Crystal Geyser were not friends. The houjicha brewed up flat, with not much of those nice sweet roasted notes that it’s known for. The flavour almost bordered on leather, but not the nice leather that’s found in some teas. Here, the sides of the tongue bitterness pops up again, which we found last week when brewing Sencha of the Earth with Evian. I find it interesting that with Crystal Geyser that unpleasant bitter note appears in the houjicha and not the sencha.

Likewise, Onsen Sui 99 also brewed a houjicha with very little roast notes. The tea was a much richer flavour than Crystal Geyser, but not with the notes one would associate with houjicha. The houjicha bordered on a sweet bread soup, tasty but odd as well.

(By sweet bread, I mean bread that is sweet. Not the organ meat. A necessary clarification? Probably not)

(Figure 210. Amber Houjicha brewed with Onsen Sui 99 on the left, on the right brewed with Crystal Geyser.)

Aiguille de pin Wakoucha

Pine Needle Wakoucha when brewed with Crystal Geyser has light pumpkin flavours and drying hay aromatics. Fortunately, Wazuka has hay drying all over the place, so I have learned this smell. There is a light bitterness, but brief, just enough to add texture to the brew. Also, there is what I can best describe as a pleasant…latex? flavour. In a good way. I swear! In reality, I’m digging around in my mind palace and I believe the actual note would be pecan.

Onsen Sui 99’s brew also has that pecan note, which is definitely not a latex note, but much more present. At least much more present for the time that it’s there, the flavour, like with sencha, disappears pretty quickly. The lingering astrigency that Onsen Sui 99 brought to the sencha is here as well, but it’s more aggressive, almost cottonmouth astringency.

(Figure 230. Pine Needle Wakoucha brewed with Onsen Sui 99 on the left, on the right brewed with Crystal Geyser.)

Gokou Matcha

Crystal Geyser brought out a strong minerality that lasted for some time. On top of that floated a rock candy sweetness, but the sweetness was not around as much as the minerality. There were also these ghosts of fruit. I wouldn’t describe it as being fruity, but it was really really trying. Overall, it was smooth, with no bitterness or astringency.

Onsen Sui 99 brought out a really smooth and creamy Gokou Matcha. Absolutely no bitterness or astringency. There were fruit notes and perhaps some floral notes as well with some wheat sweetness. The flavours lasted much longer with the matcha than many of the previous teas did with Onsen Sui 99. Still brief, but longer.

(Figure 230. Gokou Matcha brewed with Onsen Sui 99 on the left, on the right brewed with Crystal Geyser.)

Below, we have a colormap of all the teas and waters tested so far.

The Questions

We are truly messing around and doing experiments. And because of that, I think it’s much better to end these posts with questions, rather than conclusions.

Question 1: Previous research has shown that an increased calcium concentration in water will create a darker brew. Why then, with the Amber Houjicha, did Crystal Geyser, a water with higher amounts of calcium, produce a lighter brew of the two?

Question 2: The last experiment produced matcha of almost exactly the same color. At the time, we wondered if there just wouldn’t be a noticeable color difference with matcha due to it being a powder. This week, there is a noticeable color difference. Is the color of matcha determined by different factors than loose leaf tea?

Question 3: This week, Amber Houjicha did not have any of the associated roasted notes with the two different waters. Why?

I can’t wait until next time when we can add even more questions.

Expérience 1 : l'eau minérale Evian et Kirin de Shizouka

Expérience de l'eau 2 : Geyser de cristal et Onsen Sui 98

Next Experiment: Natural Mineral Water from Oita Prefecture and Acqua Panna from Italy.

Sources

Yin, Jun-Feng, et al. “Effect of Ca2+ Concentration on the Tastes from the Main Chemicals in Green Tea Infusions.” Food Research International, vol. 62, Aug. 2014, pp. 941–946, 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.05.016. Accessed 1 Nov. 2022.

Hey Tea Potatoe ;)

mon avis personnel - sans avoir fait d'autres recherches sur le calcium - est que le calcium doit soit améliorer l'extraction des polyphénols, soit modifier leur structure d'une manière ou d'une autre. J'ai récemment découvert que les polyphénols (catéchines, etc.) sont jaunâtres et deviennent encore plus bruns lorsqu'ils sont oxydés. C'est donc pour cela que le thé devient plus foncé et encore plus astringent avec le calcium, parce qu'il essaie de se coller au calcium et d'en extraire plus ou de l'augmenter d'une manière ou d'une autre. C'est une supposition très aléatoire de ma part haha.

Q1+Q3 : Je dirais que le Hojicha contient moins de catéchines, voire presque plus du tout. Peut-être que le calcium cherche d'autres composés avec lesquels réagir, de sorte que la couleur ne change pas aussi fortement ?

Il serait intéressant de savoir quel composé définit l'arôme de "torréfaction". S'agit-il toujours d'une sorte de polyphénols ou d'un composé complètement différent ? Peut-être que le calcium adhère à ce composé, ce qui réduit l'arôme.

Q2 : La couleur verte est sans aucun doute la chlorophylle. Je suppose que les polyphénols jaunes et bruns se mélangent davantage au vert de la chlorophylle, de sorte que la couleur devient plus foncée et, disons, plus boueuse. J'ai appris que la couleur chlorophylle est dominante. Le changement de couleur des feuilles d'automne est apparemment dû aux polyphénols restants lorsque la chlorophylle n'est plus produite.

Ps. J'adore ce billet et cette expérience :) Je viens de voir celui-là et je dois vérifier la première expérience aussi :)