An Overview of the Commodity and its Trade in Japan from 538 AD to 2024 AD

Jack A. Ryan

Obubu Intern #180

Foreword

About the Author and Introduction

This work is a brief primer which focuses on the commodity and trade history of tea in Japan. The impetus for the writing of this document stemmed from the author’s interest in the evolution of tea as a commodity and trade product in Japan. This document’s content has been sourced from publications which have undergone academic review. The utmost effort has gone into including the most accurate available information as of the time of writing. Any instance of information, analysis, speculation, or commentary without citation has been supplied by the author. The intent and purpose of this work is to serve as an introduction to the history of tea in Japan and to open the door for more specific investigation. Readers are advised to carefully consider any discrepancies between the information found in this primer and the many popular tellings of the history of tea in Japan.

Why Study the History of Tea in Japan?

Familiarisation with the development of tea in Japan is both an intellectual and a practical task. If one wishes to understand the how and why of contemporary Japanese tea culture it is essential to refer to the iterative developments of the past. A clear-minded and rational perspective on the past is likewise the best guide for foreseeing future development. As with many products, tea in Japan may be best enjoyed alongside its full context. Once armed with the context of history a great many dichotomies can be explored in further depth.

Pre-Modern Development of Tea in Japan: 538 AD to 1867 AD

Asuka (538-710 AD), Nara (710-794 AD), and Heian (794-1185 AD) Periods: The Chinese Origin of Tea in Japan

The apocryphal annal of Japan’s earliest history, the Nihongi, weaves a literary and engrossing tale. From the Nihongi it is evident that even prior to the rise of Tang dynasty in the 620s AD the island of Japan was firmly within the Chinese sphere of influence. 1 Buddhist monks regularly travelled to China from Japan for diplomatic and theological purposes.2 Written accounts indicate that the widespread tea culture of the Japanese clerical class was a result of this cross cultural interaction.3 Tea in these early periods was largely relegated to the realm of formalised gift-giving within the bureaucratic and religious classes and was considered a medicine rather than a beverage.4 Following Chinese practice, tea was formed into a hard brick after steaming, in a style known as dancha, and then ground up on a druggist mortar before being steeped.5 Archaeological findings and written accounts from the sinophilic court of Emperor Saga corroborate the presence of tea in Japan in the early 800s AD.6 When considering the long cultivation period for tea bushes, the numerous mentions of tea in written accounts, and the crude nature of available tea cultivation methods, all available evidence suggests the initial cultivation of tea bushes in Japan dates to the mid-700s AD. 7

Molecular archaeological analysis indicates that all the tea bushes from this early era arrived in Japan from the southern regions of China8 and that initial cultivation was undertaken by buddhist monks living in what is now Nara Prefecture.9 A series of popular legends credits two buddhist monks, Saichō (767–822 AD) and Kūkai (774–835 AD) the founders of the Tendai and Shingon schools respectively, with the initial introduction of tea seeds into Japan.10 It is highly unlikely that these stories reflect reality, however, as their travels to China in the early 800s AD were simply too late to fully account for the existing popularity of tea in the Saga court.11

Kamakura (1185-1329 AD) Period: Early Domestic Developments

While the courts of the Emperors drove much of Japan’s initial development, by 1192 AD the landowning military samurai clans had largely supplanted the Imperial family as de facto rulers.12 Although plagued by political instability, the new military government, or shōgunate/bakufu, of the Kamakura clan oversaw a “new flourishing” of many forms of high art.13 While the Kamakura were indisputably warlike they nevertheless granted patronage to intellectuals, monks, and medicine men in their court. The monk Eisai, or Yosai (1141-1215 AD), was one such favoured individual who notably contributed to history one of the earliest treatises on tea in Japan – the Kissa Yōjō ki.14 In 1214 AD, Eisai legendarily served tea to the Kamakura shōgun as a hangover cure, and the success of his remedy subsequently popularised the drink throughout the samurai military class as a medicinal beverage.15

Despite Eisai’s efforts, tea in Japan largely remained a commodity limited to the upper bureaucratic and religious classes.16 While there is limited archaeological evidence to suggest that the tools and techniques for brewing powdered tea, such as Matcha, were initially introduced to Japan during this period by Song Chinese immigrants, the vast majority of tea was still relegated to the dancha style.17 The other great development of the Kamakura period was an early commercialization of tea. Twelfth century records tell of the first taxation and trade of tea grown in Japanese monasteries.18

Muromachi (1329-1573 AD) and Azuchi-Momoyama (1573-1603 AD) Periods: Increasing Sophistication and Adoption

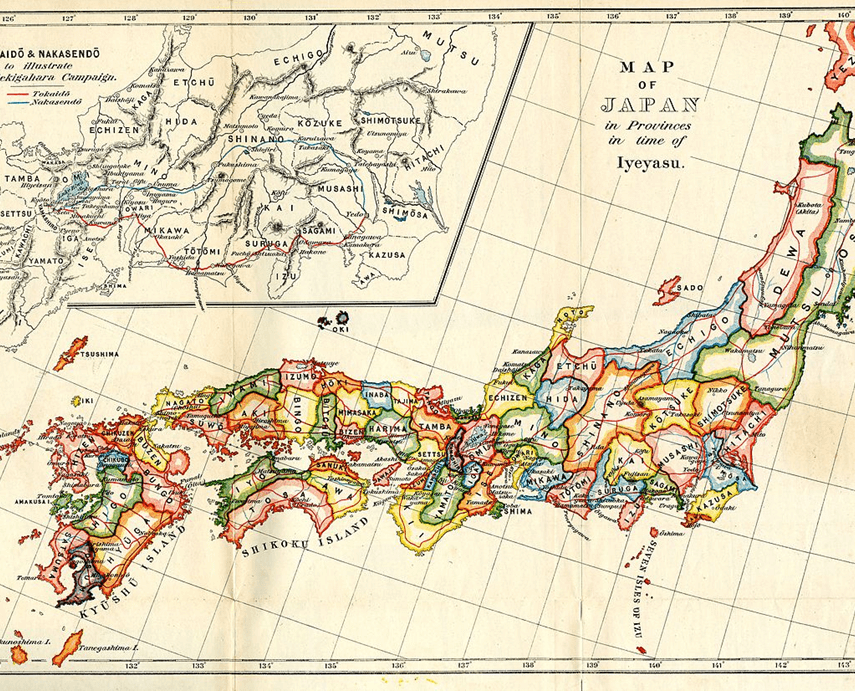

The Muromachi and Azuchi-Momoyama periods were a politically turbulent era characterised by a series of chaotic wars. The various landowning samurai military clans, headed by their daimyo, vied for the title of shōgun and thus de facto rulership of Japan. The Sengoku Jidai, or Warring States Period, dominated this era beginning with the 1467 AD Ōnin War and reaching a decisive conclusion following the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 AD.19 The increasingly complex nature of politics and warfare in the Sengoku Jidai was spurred on by a growing population, specialisation of labour, and technological sophistication.20

The fourteenth century marks a turning point in the brewing of tea in Japan as primary sources speak prominently of loose leaf, brick, and powdered styles.21 The first textual evidence of tea cultivation outside of a monastery setting is also noted in this period as “country tea,” or inaka cha, appears as a low quality, but more available counterpart to tea cultivated by monks.22 The introduction of the Chinese stone tea grinder, chausu, and the tea whisk, chasen, in approximately 1250 AD notably improved the aesthetic, textural, and flavour qualities of tea.23 By 1350 AD, tea production was widespread throughout a variety of regions and even at this early juncture there is textual evidence to suggest heady competition for the title of producing the best quality product.24 Uji Tawara would ultimately come to dominate this competition beginning in the sixteenth century.25

By the fifteenth century, tea culture was beginning to penetrate into the middle and even lower classes as free standing tea houses, chaya, began appearing in peasant villages.26 The lower classes regularly enjoyed bancha or kukicha style steeped tea as a more affordable alternative to the highly processed powdered tea.27 Specialised tea merchants appear in records during this century, both travelling and operating out of permanent shops,28 and it is very plausible that the earliest temae, or tea procedures, began with them.29 While tea was becoming more widespread the upper political class began to favour higher quality tea and increasingly associated it with sophisticated ceremonies. By the middle to late sixteenth century, intellectuals such as Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591 AD) had firmly intertwined philosophy and tea culture thus earning a place at the table of the most influential daimyo of the period.30 This initial sadō, or “Way of Tea,”31 led to a culture of ever evolving and competing art forms concerned with the preparation and enjoyment of tea. Sadō continues in various forms into the contemporary period.

Edo Period (1603-1868 AD): A Golden Age

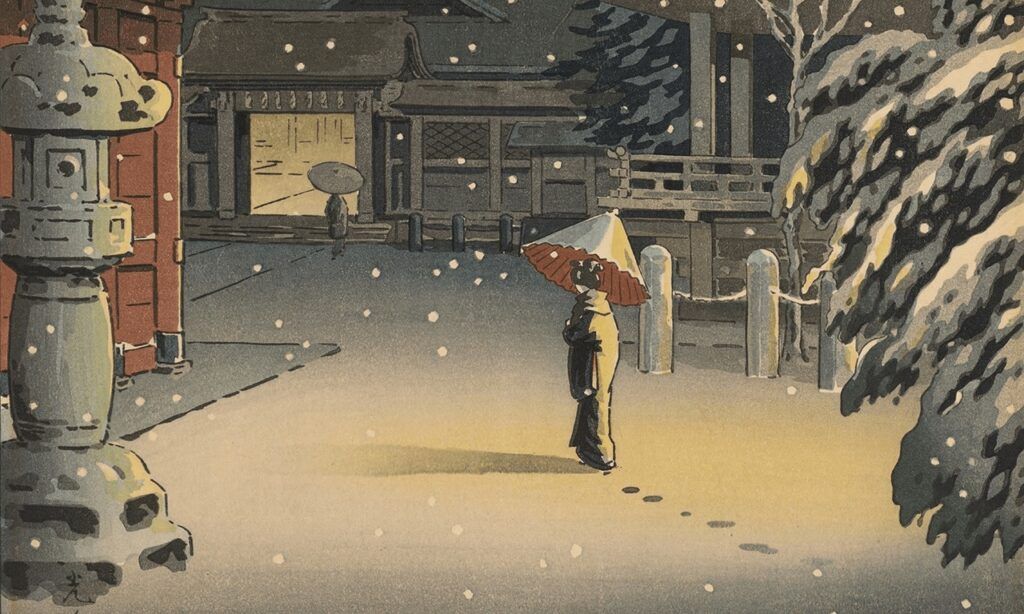

The widespread decentralisation, chaotic opportunity, and violence which characterised the Sengoku Jidai was abruptly replaced by a strict ossified social hierarchy enforced across Japan by the victorious Tokugawa bakufu. This unprecedented centralization along with the sudden urbanisation of the court in Edo demanded a new level of agricultural industriousness and domestic commercialization.32 While the shōgunate would ultimately atrophy and begin to decay in its self-imposed international isolation, a result of the infamous Sakoku policy,33 there were several significant developments in tea production designed to meet the luxurious demands of the urbane classes.

The tea trade of the mid-seventeenth century became characterised by a notable increase in domestic exchange and shipping of tea. Even the far northern provinces took to importing “truly huge” quantities of processed tea.34 By the early eighteenth century, the mass cultivation of tea was actively pursued across Japan enabled by a class of increasingly specialised workers, merchants, and middlemen. Cultivation techniques became more formalised and by, at latest, 1587 AD the ōishita saibai, or roof-over method, was being practised in Uji.35 This practice protected the tea bushes from pests and frost, but also engendered a greater degree of sweet and umami flavour into the final product. This wave of mass cultivation included the colder northern provinces in which specialised cultivation techniques, such as shaping the bushes into closely packed round rows, were developed to combat the less suitable climate.36 Perhaps one of the greatest triumphs of the Edo period was the development of Sencha by Nagatani Yoshihiro, or Sōen (1681–1778 AD), in 1738 AD.37 Sōen’s creation inspired a monk named Baisaō (1675–1763 AD), who began spreading his “Way of Steeped Leaf Tea” across Japan via his tea shop in Kyoto, thus widely popularising Sencha.38 By the turn of the Nineteenth century, Japan had a growing consumer society, a hardworking captive labour force, and a thirst for increasingly delicious tea products.39

The Nineteenth century saw another substantial development in tea cultivation. In the 1830s AD, the iterative development of practices used in the cultivation of Sencha resulted in the creation of Gyokuro, or “jewelled dew,” in Uji Tawara.40 Sakamoto Tōkichi (1681–1778 AD) is often named as the figure who formalised the techniques used in Gyokuro production, although he cannot be exclusively credited with its creation.41 The abundance of textual evidence, the increasing presence of tea shops in cities, the development of tea-infused food types, and the production of sophisticated advertisements in the mid-nineteenth century all point to tea becoming “an integral part of everyday life and probably imbibed by almost all residents of the archipelago.”42

Modern Development of Tea in Japan 1868 AD to 2024 AD

Meiji (1868-1912 AD) and Taisho (1912-1926 AD) Periods: Ambitions Abroad

The self-imposed isolation of the Tokugawa bakufu was gradually ended by the increasing presence of European and North American fishing, merchant, and naval vessels in East Asia. The King of the Netherlands, whose nation was the only European power allowed any presence in Japan by the Tokugawa, warned the shōgun of the dangers of isolationism via a letter written in 1844 AD.43 In 1846 AD, an initial American effort to negotiate trading rights with Japan led by Commodore James Biddle was turned away by the shōgun’s officials. A more substantial expedition undertaken by Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s East India Squadron from 1852 AD to 1854 AD, however, could not be so easily rebuffed.44 Perry’s aggressive negotiations resulted in the unprecedented Treaty of Kanagawa which granted the United States access to the Japanese market.45 Follow-along treaties allowing the French, Russian, Dutch, and British access into Japan soon followed.46 With many of Japan’s southern domains already resentful of Tokugawa rule, the shōgun’s outrageous submission to the imposition of foreign barbarians prompted the Satsuma, Chōshū, and Tōsa domains to modernise their own military forces with Western European equipment and training in 1863 AD.47 Toppling the bakufu in short order following a brief civil war in 1868 AD, the alliance of rebellious domains “restored” the power of the young Emperor Meiji and began a campaign of rapid modernization designed to bring the Empire of Japan into parity with the Western European and North American powers.48

The origin and character of the Meiji government is significant to the history of tea in Japan because their developmental policies would ultimately shape the modern Japanese tea industry. Surpassing the military and economic capacities of the other major global powers was the Empire of Japan’s new raison d’être. Quickly breaking into the international market, Japan first began exporting substantial quantities of tea in 1859 AD following the signing of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Japan and the United States.49 The Japanese government rapidly adopted an export focused trade policy designed to enrich the state and finance industrialization. Alongside silk and coal, tea would become one of Japan’s top exports with the primary trading partner being the United States.50 The need to produce large quantities of tea for export rapidly altered tea production: factories were centralised in port cities, mountainsides were abandoned in favour of flatlands, and standardised agricultural practices were disseminated by state agencies.51

In the first years of the Meiji period, Japan produced 9,522 tons of tea.52 By the end of the First World War, in the mid-Taisho period, 38,434 tons of tea were being produced.53

A median of sixty six percent of all Japanese tea production was exported during this era.55 In the late nineteenth century, state sponsored organs such as the National Tea Production Experiment Station and Organization for Progress in Tea Processing brought about the standardisation of hand processing methods56 through the dissemination of best practices and agricultural fairs.57 Wakoucha, or Japanese Black tea, and Oolong were added to the repertoire of production following the insistence of the Lord of Home Affairs, Ōkubo Toshimichi (1830–1878 AD), but export attempts were largely halted after the international market showed more interest in Sencha – which formed the vast bulk of all exported types.58

Mechanization enabled a decline in tea cost, the expansion of production output, and the rapid increase of labourer wages.59 Takabayashi Kenzō (1832–1901 AD) developed the first working prototype of a seicha massatsuki, or “tea processing friction machine,” in 1885 AD.60 Despite receiving one of Japan’s first private patents for his invention and doing a fair amount of advertising, the high cost, small capacity, and limited functionality of the initial machine prevented it from gaining traction.61 Following Kenzō’s example, Mochizuki Hatsutarō invented a device for rough rolling and one for crumpling tea in a rotating manner in 1900 AD.62 Usui Kiichirō, around the same time, developed another device for fine, or soft, rolling.63 In 1915 AD, Akiba Yasukichi made a great improvement by perfecting an automatic steamer.64 In the realm of harvesting, Sakai Jinshirō (1842–1918) popularised the use of harvesting scissors, as opposed to handpicking, but the tool did not gain traction until 1918 AD due to quality concerns.65 Ultimately the use of harvesting scissors, with additional modifications such as an attached bag, became ten times more efficient than hand picking.66

Once these various machines were combined into a complete system by farmers mechanisation began in earnest.67 The era of te-momi-seiho, or manual processing, was gradually outmoded by han-kikai-seiho, or semi-mechanized processing, around the 1910s AD.68 Kekai-seiho, or completely mechanised processing, was widely adopted by the tea industry in the 1930s AD.69

Shōwa Period (1926-1989 AD): A Shifting Landscape

Japan’s foreign policy during the late Meiji and Taisho periods prioritised expanding the Japanese sphere of influence across the Pacific. The Invasions of Taiwan (1874/1895 AD), the invasion of Ryūkyū (1879 AD), the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895 AD), the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905 AD), the Colonisation of Korea (1894-1910 AD), and Japan’s limited but fruitful participation in the First World War on the side of the victorious Entente (1914-1918 AD) secured the Empire’s status as a global power.71 In the reign of Emperor Shōwa, however, the Japanese military officer-core, flushed with success and influence, began to dominate the civil government and steer the Empire into a state of constant, total war, for complete regional domination – culminating in Japan’s disastrous participation in the Second World War as a belligerent of the Axis Alliance.72 This political development in the Empire, naturally, had an impact on both the international tea trade and domestic tea production. Export growth slowed substantially, fertiliser was abandoned due to wartime scarcity, chemical pesticide agents became more prevalent, and botanical research was largely halted.73 Tea maintained a strong domestic presence, however, and even during the strictest periods of wartime austerity the drink was widely available to the Japanese public.74

The end of the Second World War, and the subsequent occupation of Japan by the United States, largely reversed the aforementioned trends in cultivation and research. Ever increasing mechanisation, including full automation, and high domestic demand spurred on by a renewed cultural consumerism drove tea production to new heights in the post-war era.76 The 1960s AD and 1970s AD introduced a generation of processing machines which were more reliable, accommodated a higher capacity, and ran with greater efficiency than ever before.77 Harvesting also benefited from increased mechanisation. In 1950 AD in Nara, a motorised picker was developed which doubled the efficiency of the old harvesting scissors.78 In 1965 AD, Matsumoto Machines developed a manually operated two person mower which doubled the efficiency of the motorised picker.79 By 1970 AD, the first self-propelled rideable mowers for use on flat ground were developed which provided six to eight times the efficiency of a motorised picker.80

Tea faced its first serious competition from coffee in the 1960s AD, however, and by 1975 AD Japan became the world’s third largest importer of the drink.81 Wakoucha, which had formally survived at a small scale in the domestic market, was rapidly outmoded when import barriers were lifted in 1960 AD and an influx of foreign Black tea caused local production to collapse.82 In order to maintain a growing market for tea, Corporate organisations, such as the ZenNihon Chashō Kurabu, or All-Japan Tea Merchants’ Club, worked to associate tea drinking with traditional culture via advertising campaigns.83 These campaigns were quite successful and the domestic market continued to thrive until the economic crash of the 1990s AD.84

Heisei (1989-2019 AD) and Reiwa Periods (2019- AD): An Uncertain Future

Perhaps the most significant development of the Heisei period was the development of plastic (PET) bottled tea by the manufacturer Itoen in 1990 AD.85 Plastic bottle tea quickly dominated the domestic market due to its convenience and accompanying effective advertising campaigns.86 The majority of Japanese tea production now serves to supply the plastic bottle tea industry.87 Computer and digital technology has also improved the efficiency of manufacture88 even as the number of households producing tea declined by 90% from 1970 AD to 2001 AD.89

Since the post-Taisho period decline, Japanese tea exports never truly recovered and only a small minority of production makes it to the international market.90 In the post-war Shōwa period, a median of only nine percent of tea production in Japan was exported.91 Since the beginning of the Heisei period, a median of a mere one and a half percent has been exported.92 There has been a slight upwards trend in export since the 2010s AD93, however, with social media and increasing globalisation stimulating the international market’s interest in Japanese tea. Formally low demand tea types, such as Wakoucha, seem to have regained a toehold niche in the domestic market. It remains to be seen how the Reiwa era’s ageing population of tea farmers and the increasing centralization of tea production will affect the future of tea in Japan.

- Jonathan Clements, “A Brief History of Japan: Samurai, Shōgun and Zen: The Extraordinary Story of the Land of the Rising Sun,” (Tuttle Publishing, 2017): 59. ↩︎

- Farris, “Bowl for a Coin,” 9. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 10. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 14. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 16. ↩︎

- William Wayne Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin: A Commodity History of Japanese Tea,” (University of Hawaii Press 2021): 9. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 10. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 8. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 9. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 9. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 10. ↩︎

- Clements, “A Brief History of Japan,” 101. ↩︎

- Clements, “A Brief History of Japan,” 108. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 24. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 24. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 27. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 23-24 ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 28. ↩︎

- Clements, “A Brief History of Japan,” 133. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 34. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 37. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 38. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 38-40 ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 45. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 59. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 58. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 86-87. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 62. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 63-64. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 71. ↩︎

- arris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 71. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 73-74. ↩︎

- Clements, “A Brief History of Japan,” 150. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 75. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 70. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 80-82. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 92. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 93. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 97-98. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 94. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 94. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 108. ↩︎

- Clements, “A Brief History of Japan,” 160. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 125. ↩︎

- Clements, “A Brief History of Japan,” 165. ↩︎

- Clements, “A Brief History of Japan,” 166. ↩︎

- Clements, “A Brief History of Japan,” 168-172. ↩︎

- Clements, “A Brief History of Japan,” 172-174. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 126-127. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 127-129. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 128-131, 136. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 133. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 133. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 133. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 133. ↩︎

- Masahiko Shintani, “Technological Progress in the Tea Manufacturing Industry in Japan,” (Hitotsubashi Journal of Economics, vol. 32, no. 1, June 1991): 24. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 144. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 141-142. ↩︎

- Shintani, “Technological Progress,” 21. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 139-140. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 140. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 140. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 140. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 140. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 136. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 136. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 140. ↩︎

- Shintani, “Technological Progress,” 22. ↩︎

- Shintani, “Technological Progress,” 26. ↩︎

- Shintani, “Technological Progress,” 23. ↩︎

- Clements, “A Brief History of Japan,” 186-193. ↩︎

- Clements, “A Brief History of Japan,” 194-200. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 147-149, 151. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 157. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 133. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 154. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 155. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 152. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 152. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 156. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 157. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 152. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 158-159. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 159-160. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 162. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 163. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 163. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 164. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 161. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 162. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 133. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 162. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 162. ↩︎

- Farris, “A Bowl for a Coin,” 162. ↩︎

Bibliography

Clements, Jonathan. A Brief History of Japan: Samurai, shōgun and Zen: The Extraordinary

Story of the Land of the Rising Sun. Tuttle Publishing, 2017.

Farris, William Wayne. Bowl for a Coin: A Commodity History of Japanese Tea. UNIV OF

HAWAII PRESS, 2021.

Shintani, Masahiko. “Technological Progress in the Tea Manufacturing Industry in Japan.”

Hitotsubashi Journal of Economics, vol. 32, no. 1, June 1991, pp. 21–38.