My name is Emma, intern #162, from Denmark.

During my time at Obubu and Japan my interest for the Japanese culture grew bigger and especially the history behind the traditional tea garments caught my attention.

During my time at Obubu, I wanted to explore the traditional garments worn in relation to tea. Which uniform is worn during the tea ceremony and why? What does the kimono symbolize? What is the history behind the samue and the kimono?

To answer these questions, I have in the following written a short and condensed article on the subject, where I try to answer the questions mentioned above and discover the history behind traditional tea garments, and its influence and importance for the Japanese (tea) culture.

The History of the Kimono

Derived from the words ki (wear) and mono (thing), kimono translates to “wearing thing”. Originally kimono referred to all clothing in general, but in the recent years the word has been used to refer specifically to traditional Japanese clothing.

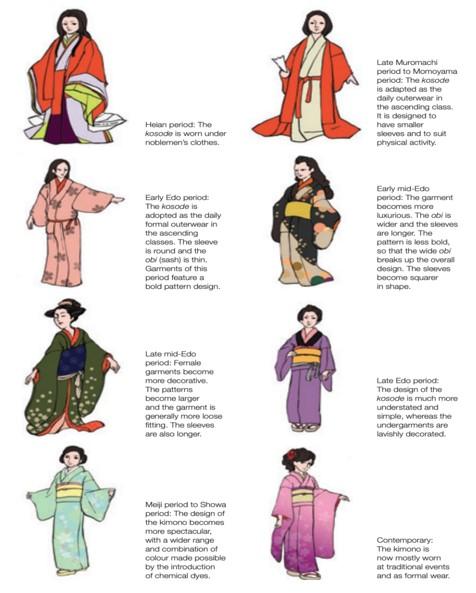

The garment has had many names, but it was not before the Meiji period (1868-1912) that the garment was called kimono. The design of the kimono as we know it today came into form during the Heian period (794-1185).

During the Heian period a new design technique was developed for the kimono. Straight cuts of fabric were sewn together to create a garment that fit every type of body shape and the seamstresses hereby did not have to concern themselves with the shape of the buyer’s body.

The straight lines and cuts of the kimono made the garment adaptable for all seasons and weather. The garment could be worn in layers to provide warmth in winter, and its breathable fabric, such as linen, were comfortable in summer. The kimonos practical advantages helped it become a part of Japanese people’s everyday lives.

In the Heian period the practice of wearing kimono in layers came into fashion and the Japanese people began paying attention to how kimono of different colors and prints looked together. Hereby an interest in the color combinations developed and how it either could represent a season or the political class to which the wearer belonged. The garments that people wore therefore began to differ depending on their social status as either a member of nobility or a common citizen. The nobility of the Heian period began to wear clothing that covered their hands and feet, which made it difficult to move in, while the common citizens wore clothes more like modern clothing, with straighter sleeves and better mobility.

When Japan entered the Kamakura period (1185-1333) and the Muromachi period (1336-1573) it became common for both men and women to wear bright colored kimono. During these periods the warrior class grew in power, and the warriors would go to the battlefield dressed in bright colors that represented their leaders.

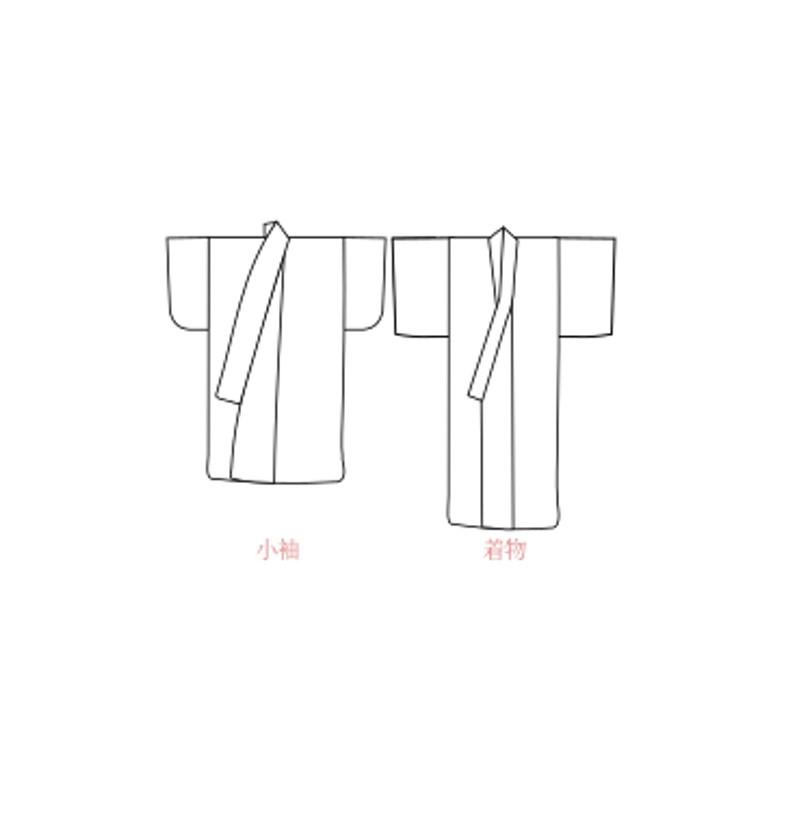

During the Edo period (1603-1868) the traditional garment became known as a kosode. This term directly translates to “small sleeves” as the armholes of the original design decreased in size. Like most societies in this decade, Edo period Japan was stratified. The kosode played an essential role in stratified Japan, as all Japanese people, despite social rang, age or gender, wore it. The garment was thus used to represent and express individuality. The population used the kosode to describe themselves and they adopted ways to customize their kosodes. The style, motif, fabric, technique, and color all symbolized different character traits and social statuses, and they all helped to describe the wearer.

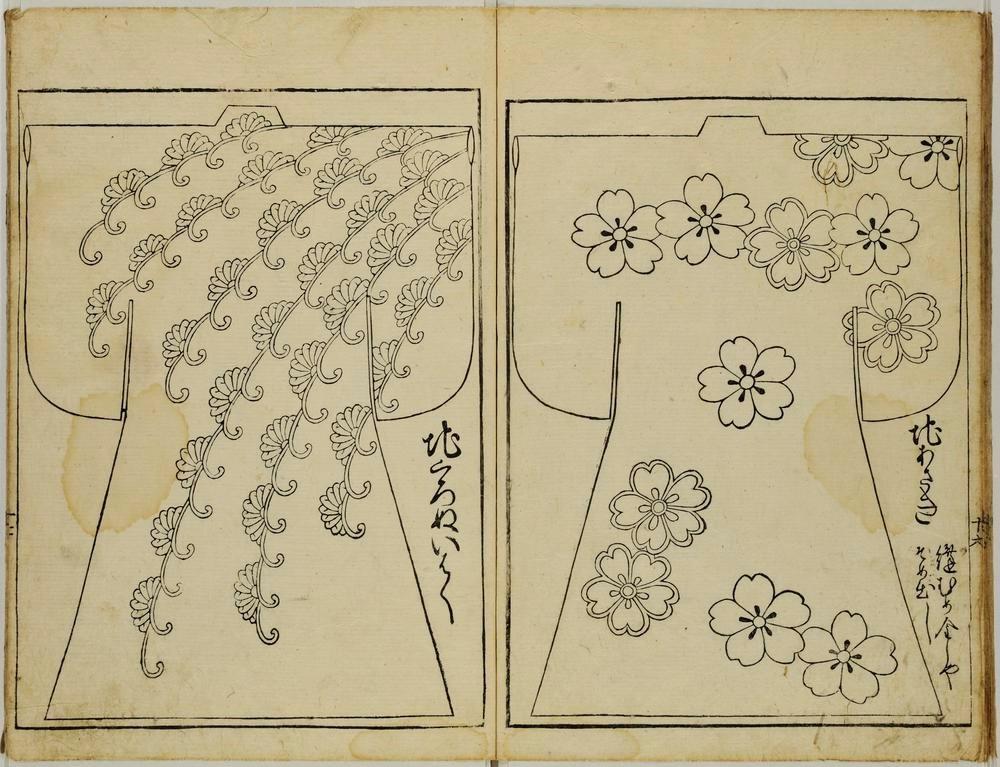

The quality, choice of pattern and thread of the kosodes consistent parts also has great significance for the person it is representing, and were essential criteria for presenting the rank, age, gender and refinement of the person wearing it. For example, the cherry blossom design was not just a pretty design, but symbolized mortal feminine beauty, and use of Kanji and scenes from classical Japanese and Chinese literature expressed literary prowess.

The techniques behind the making of the kosode rapidly developed and there were so many details in early modern kosode, therefor the design books, called Hinagata bon, were essential and everyone used them. The Hinagata bons written by the most respected artists from this period emphasizes, how kosode were actual works of art and that each individual garment was the biodata of its wearer. In the same way, kosode from the Edo period is the biodata of an age. Because the Japanese wore this artwork, the early modern Japanese left a remarkable insight into the past Japanese society and their values before foreign influences.

In Meiji period (1868-1912) the kosode evolved into the kimono and unlike earlier the kimono was predominantly worn by women. Japan was heavily influenced by foreign cultures during the Meiji period and the government encouraged people to adopt the western clothing and habits. Government officials and military personnel were required by law to wear western clothing for official events. However ordinary citizens, and women in particularly, were required and encouraged to wear kimonos decorated with their family crests (kamon), which symbolized and represented their family backgrounds, to formal events. In spite of these changes the main purpose, to visually communicate and represent a message and biodata, of the garment remains unchanged – even today.

The reason why the kimono became so important to post Edo Japan is that the garment kept a part of traditional Japan alive and relevant in a time with rapid modernization and foreign influence. So as the country was undergoing fundamental changes, the women wearing the kimonos created a reassuring visual image and it also became a silent symbol and link between women as mothers and cultural guardians. Today the kimono is a visual reminder of Japan’s core culture before its modernization.

In the present-day Japanese people rarely wear kimonos in everyday life, and reserves them for formal events and occasions, such as weddings, funerals, coming of age ceremonies and university graduation.

Iromuji

The kimono is also worn at tea ceremonies. There are many different variations and styles of kimonos, and the style worn at tea ceremonies is called iromuji. The traditional tea ceremony has many rules, and there are also rules for what kind of clothes that are suitable to wear.In the tea ceremonies the garments worn are usually plain and not flashy as nothing should distract the attendants from the tea experience. The fabric of the iromuji is therefore dyed in one single color, with no dyed patterns or embroidery on it.

The iromuji usually comes in solid colors, but it can also be decorated with a jimon, which is a woven pattern in the fabric.

Even though it is most communally worn at tea ceremonies, it can also be worn at a variety of formal and casual events depending on the number of crests, accessories and color.

When it is used as casual day wear or at dinner with friends the wearer can play more with the accessories by choosing a more personal or fashionable obi (belt) to create a more personal and fun look or choose an obi in the same tone as the iromuji to create a more sophisticated look.

When this style is worn at formal events, iromuji with brighter colors, for example pink and yellow, and jimons symbolizing positivity are considered suitable to attend weddings, tea- and graduation ceremonies, while iromuji with neutral colors, for example dark blue or grey, are suitable for funerals.

The Samue

The samue is a Japanese traditional workwear, and translates directly to make-doing-clothes (sa= make, mu=doing, e=clothes). The garment deprives from the Buddhist Zen monks, thought the Buddhist monks are often seen wearing robes and kimonos, these garments are not practical when engaging in physical chores around the temples. The chores around the temple involve chopping threes and sweeping. These chores are a part of the zen monks practice called samu (make – doing), so the samue was created to be worn while practicing samu.

The samue is a functional garment that has its roots in the kimono, and its functional and simple design makes it easy to wear while doing physical labor and reduces the risk of accidents, as its short sleeves and drawstrings secures that everything stays in place and that nothing gets in the way.

In the early days the garment only included the top part, but with time the pants entered the picture.

The samue is created in regions with a long tradition of cotton weaving, such as Kurume in Fukuoka and Osaka (Japan’s historic textile center). The garment is made from high-quality fabrics that reflect the centuries long history of Japanese textile. The fabric used to create the samue can for example be the wazarashi cotton, which is the traditional Japanese method of cotton scouring that requires the cotton to spend four days in a cauldron, or tsumugi cotton, which comes from Kurume and requires usage of multiple threads to create delicate patterns.

Since the samue was originally designed as Japanese traditional work wear, they have been adopted for practical use in many fields, hereby craftspeople and artist. It is today very common for Japanese people to wear samue in studios, workshops or offices.

Zen Buddhist still wear the samue, and if you visit or stay at a temple and do zazen, a meditative discipline, you will discover that the samue is preferred for zazen meditation practice. Other traditional practices having connections to Zen Buddhism also uses the samue, and is often worn during tea ceremony, by calligraphers or traditional musicians.

The samue also represents a point of contact between modern and traditional Japanese culture. When wearing the samue in present day you are reminded of the ancient times and traditions, and hereby the memoirs and traditions of traditional Japan is still seen in the present day.

The traditional Japanese garments worn in relation to tea are used as a symbol for the preservation of the ancient Japanese society and its traditions. When the garments are worn by the Japanese population they represent their former traditions, values and their importance for the modern Japanese society’s self-understanding.

Sources:

https://web-japan.org/kidsweb/virtual/kimono/kimono01.html

https://daily.jstor.org/the-surprising-history-of-the-kimono/

https://mymodernmet.com/japanese-kimono/

https://www.tsunagujapan.com/10-different-types-of-kimono-for-women/

https://shop.japanobjects.com/blogs/editorial/samue

Thank you for writing about the samue! Interesting article.

On my first trip to Japan I discovered a second-hand kimono shop, and have been in love with Kimono since. There is so much to learn about kitsuke (the way you wear kimono) that I’m still learning something new after 7 years.

I hope you keep up the interest too.