How to use this guide

You may follow the story chronologically, from its roots to its buds, or choose your Brewer from the menu to unroll their scroll. At any point, you may change your Brewer, or linger for the 2nd brew, a deeper infusion from the same lives.

The guide also carries a Google Map tracing the sites in Kyoto and neighbouring lands, where these lives and leaves intertwined. To set out, scan the QR code or tap Start Pilgrimage.

This work has been soaked in the care of the entire Obubu family. My special gratitude flows to KD (#201), who poured the inspiration for the pilgrimage route, and to Izzy (#200) for inspiring the brewers’ appearance with her impeccable vibe. At the close of the gathering, it is Kira (#208) who bows, hands lowered after the final cup is served.

CHOOSE YOUR BREWER

Chapter 1. Saichō, Kūkai and the Sinensis Root

In the early 9th century, two Japanese monks set sail for Tang dynasty China.

They would return with seeds — both spiritual and botanical.

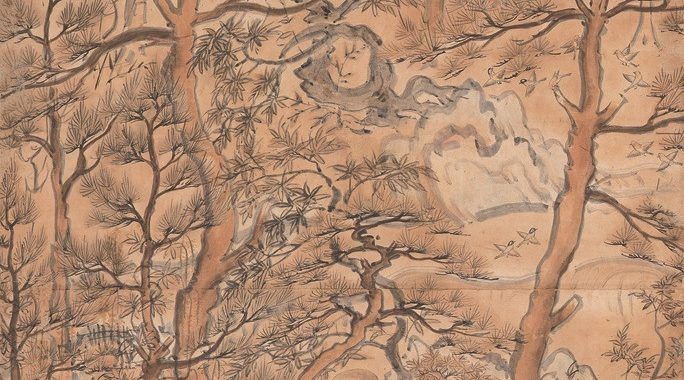

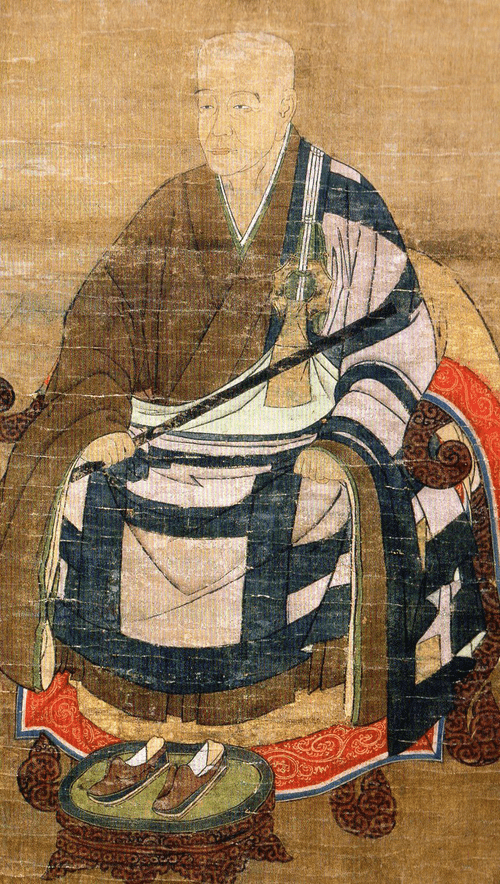

Saichō (767–822), posthumously known as Dengyō Daishi, founded the Tendai school of Mahayana Buddhism. Grounded in the Lotus Sutra, he taught that all beings possess Buddha nature and broke Nara’s monopoly on ordination. At the heart of Tendai practice lies shikan (止観) — training the mind first to become still, then to gain insight into the nature of reality, cultivated through both seated and walking meditation. After returning from Mount Tiantai in 805, he planted the seeds near Enryaku-ji, at the foot of Mount Hiei [1].

Kūkai (774–835), later known as Kōbō Daishi, founded the Shingon school of esoteric Vajrayāna, aimed at sokushin jōbutsu (即身成仏) — becoming a Buddha in this very body through the union with Dainichi Nyorai. After receiving transmissions in the capital of the Tang dynasty, he returned to Japan in 806 with mudras, Siddham script (bonji, 梵字), mandala art, and crucially, tea seeds and a stone mill. These seeds took root at Butsuryū‑ji in Uda (Nara), under the direction of his disciple Kenne. Today, the temple is revered as the cradle of Yamato tea, and the Tang mill remains enshrined there as a sacred relic [2, 3].

Shortly after, the Tendai monk Eichū served brewed tea to Emperor Saga, marking the first imperial record of tea drinking [4]. By then, the tea was compressed brick tea “dancha” (団茶), prepared by shaving and boiling, reserved for the court and monastic circles. The emperor then ordered tea to be planted in Kinai and neighbouring provinces.

Later, he would express his delight in a poem after drinking tea with Kūkai [5]:

“Sharing fragrant tea, we lose the day to dusk”

But after this fragrant moment, silence. No new plantations were cultivated. Court interest shifted to perfumes and poetry. And even though tea gardens in Shiga and Nara persisted, tea remained a relic of temple precincts. Furthermore, the rituals that once included tea offerings gave way to more accessible rites. The traditions Saichō and Kūkai sowed remained buried, like seeds under frost, awaiting renewal [6]. It would take another monk, also returning from China, to awaken the leaf once more.

References

- Hiyoshi Taisha official website

- Eight Patriarchs of the Shingon Sect of Buddhism: Kūkai / ColBase–Nara National Museum (CC BY 4.0)

- Nara Prefecture Historical and Cultural Resources Database “Butsuryū-ji”

- Nihon Kōki [日本後紀]. Entry dated Kōnin 6 [815], Fourth Month, Day 22

- Keikokushū [経国集]. 827

- Frosted tea fields shot by Matsu-san

Chapter 2. Eisai and the Healing Leaf

In the late twelfth century, Eisai (1141–1215), later known as Myōan Eisai Zenji, traveled twice to the Southern Song. His second voyage in 1187 took him to Jingde monastery, where he immersed himself in the Linji school of Chan Buddhism, which will become known in Japan as Rinzai Zen.

Rinzai training stressed the sudden awakening (tongo, 頓悟), attained through direct experience rather than gradual cultivation of the Sōtō school. Monks were tested with paradoxical riddles (kōan, 公案), designed to push the mind beyond conventional reasoning. Eisai observed the monks drinking whisked powdered tea (mocha, 抹茶) before meditation to sharpen concentration and sustain long hours of sitting [1].

A tea-flavored kōan appears in the Rinzai compilation assembled shortly after Eisai’s death [2]:

Master Zhàozhōu asks a monk whether he has been here before. Whether the monk answers “yes” or “no”, the reply is the same: “Go have tea”(kissa ko, 喫茶去)

In 1211, Eisai wrote Drinking Tea for Health (Kissa Yōjōki, 喫茶養生記), the oldest Japanese treatise on tea, and presented it to shogun Minamoto no Sanetomo [3].

It opens with the words:

“Tea is the health elixir, the sage art of prolonging life”

Eisai’s revival of tea established it both as a healthy drink and a companion to Zen training. After returning to Japan, he planted some of the Song seeds at Kennin-ji, the temple he founded in Kyoto, while entrusting the remaining seeds to the supporting temples, most notably including Myōe’s Kozan-ji [4].

References

- Genkō Shakusho (元亨釈書), 1322.

- Wudeng Huiyuan (五灯会元), juan 4, p. 281a.

- Eisai, Kissa Yōjōki (喫茶養生記, “Drinking Tea for Health”), 1211

- Kozan-ji official website

Chapter 3. Myōe and the Visionary Seed

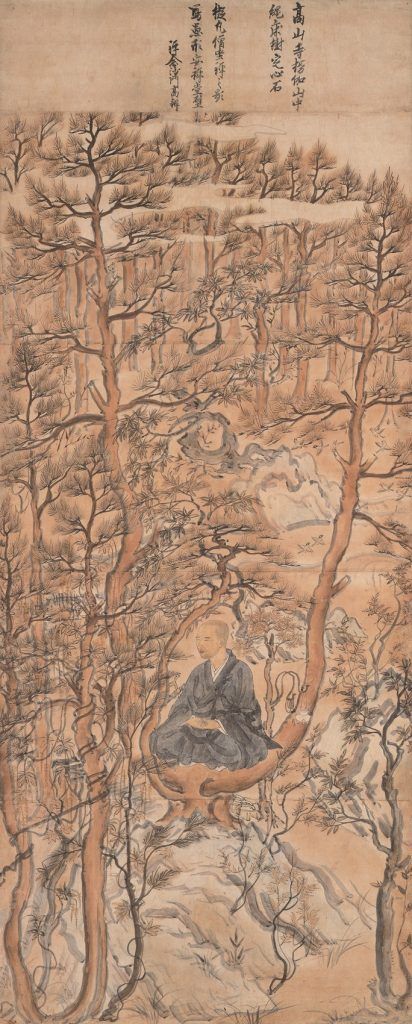

Myōe (1173–1232), posthumously Kōben, was a leading monk of the Kegon school of Mahayana Buddhism. Kegon emphasises the interpenetration of all things through the Flower Garland Sutra as the ultimate teaching of the Buddha.

A devoted scholar and reformer, Myōe composed over fifty works, revived monastic discipline, and promoted the recitation of the Mantra of Light [1].

For more than forty years, he recorded his nightly visions in the Dream Diary (Yume no Ki, 夢記). One entry reads [2]:

“In the deep mountain mist, the sound of a horse’s hooves echoes through the valley”.

At dawn, following the echoes, Myōe discovered a slope of soft, well-drained earth bathed in morning fog. Seeing this as a sign from the mountain kami, he planted there the tea seeds entrusted to him by Eisai [3].

Over time, Toganoo became celebrated as honcha (本茶, true tea), while lesser leaves were marginalized as hicha (非茶, false tea), and tasting contests emerged to tell true leaf from false. Myōe encouraged his monks to drink tea before meditation and advised local farmers on tea cultivation in Uji, while his disciple Jisshin Shōnin carried the seeds further, planting them on the slope of Mt. Jubu in Wazuka [4].

References

- Genkō Shakusho (元亨釈書), 1322

- Myōe, Yume no Ki (夢記, “Dream Diary”), entries 1191–1231

- Kōzan-ji Chaen Yuraiki (高山寺茶園由来記)

- Wazuka Town cultural history page

Chapter 4. Sen no Rikyū and the Irregular Bowl

Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591) whisked centuries of tea preparation, presentation and enjoyment into sadō (茶道) — The Way of Tea, sometimes rendered as Teaism. His practice found home in the precincts of Daitoku-ji, back then the center of the Rinzai tradition.

Serving Oda Nobunaga and later Toyotomi Hideyoshi as the tea master to the court, Rikyū shaped the Japanese tea ceremony into a spiritual once-in-a-lifetime encounter (ichigo ichie, 一期一会).

The approach to the tearoom was modeled after shrine pilgrimage: guests followed the garden path (roji, 露地), paused to cleanse hands and lips at the stone basin (tsukubai, 蹲踞), and entered through the middle gate (chūmon, 中門) [1].

“Once you pass through the garden and the gate, you must forget the affairs of the world and return to a beginner’s heart”.

Hideyoshi’s portable golden tea room had walls, shelves, and even ladles covered in gold leaf, intended to awe guests and display wealth [2, 3].

In contrast to the ruler’s taste for grandeur, Rikyu expressed his art through wabi-sabi (侘寂): the beauty of imperfection, impermanence and humility.

His tea huts shrank to just two tatami mats, and even the mightiest lords had to crawl through the entrance (nijiriguchi, 躙口). Inside, rustic Raku ware, born from Chōjirō’s kiln at his request, replaced Chinese porcelain [4].

In hindsight, the clash of visions was inevitable. While the exact reasons remain debated, in 1591, Hideyoshi ordered Rikyū to commit seppuku.

On his final morning, Rikyū hosted one last tea gathering. After the bowl was complete, the tea master lifted the vessel and struck it; the fragments scattered across the tatami. Then he bowed and admitted death into the tearoom as his final guest [5].

References

- Nampōroku (南方録), Nanbō Sōkei, early 17th c.

- Taikōki (太閤記), Oze Hoan, 1626.

- Replicated golden tea utensils from the Golden Tea Room (Taishi.jpg) by ブレイズマン / CC BY-SA 3.0

- Raku-ke Monjo (楽家文書), late 16th–early 17th c.

- Taikōki (太閤記), 1591 entry.

Chapter 5. Ingen, Baisao and the Wandering Branch

In 1654, the Chinese monk Yinyuan Longqi (Ingen Ryūki, 1592–1673) reached Japan. With him came a distinct Ming liturgy featuring Chinese-style chanting, calligraphy, temple layout, vegetarian Buddhist cuisine (Fucha ryori, 普茶料理), and crucially, a new way to brew tea known as encha (煎茶) – infusing loose leaf in hot water. Despite the shared lineage with Rinzai, Ingen’s Zen branched into the Ōbaku school in Japan that established its headquarters at Manpuku-ji in Uji [1].

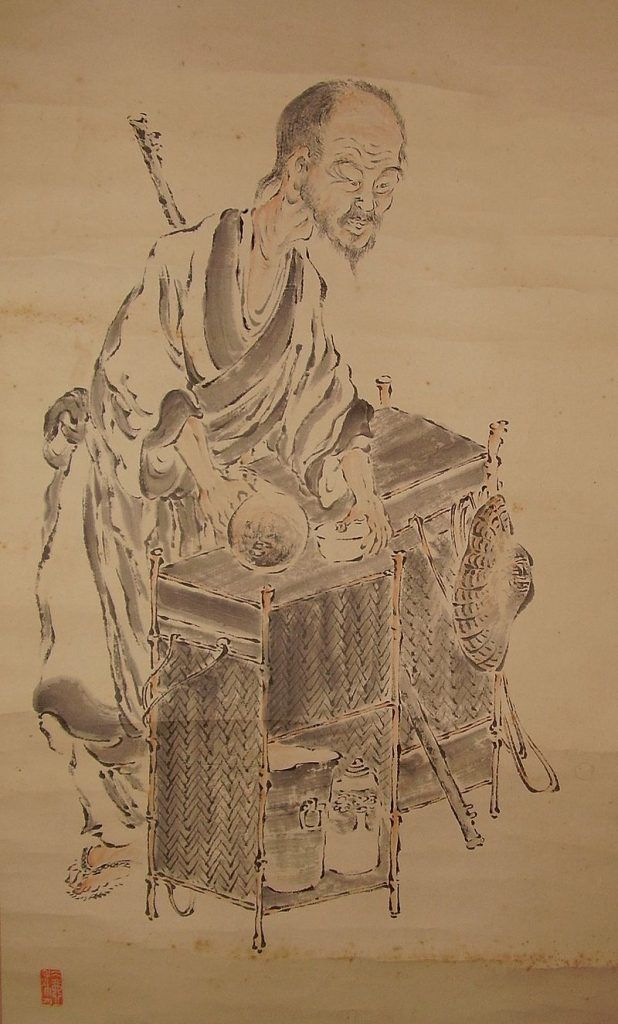

A generation later the monk Gekkai (1675–1763) stepped out of Manpuku-ji into the Kyoto city. Renouncing the monastic life, he would become known as the Old Tea Seller (Baisaō, 売茶翁) [2, 3].

“I know nothing of the world, nor do I know Zen.

I shoulder my kit and brew tea wherever I go.

If no one comes, I sit by the stream with my basket”

With his portable bamboo kit on the Kamo riverbanks, in Tadasu no Mori, and at Arashiyama, Baisao brewed tea while composing his Twelve Impromptu Verses at the Tea Stall. His gatherings popularized loose-leaf tea and fostered an unpretentious style that appealed to Kyoto’s literati [4].

At the end of his life, he burned his utensils, refusing to let them become relics in a cult of old masters’ tools [5]. Ironically, though he despised the stagecraft of sadō, his followers codified his free kettle into yet another “Way” — senchadō (煎茶道) [6].

References

- Ōbaku-san Manpuku-ji Engi (黄檗山萬福寺縁起), 17th c.

- Daiten Kenjō, Baisao-den (売茶翁伝), 1763.

- Baisao, Baisao Gego (売茶翁偈語), 1763.

- Baisao Nenpu (売茶翁年譜), Edo period chronology.

- National Diet Library, “Baisao” entry

- Ryūkatei Ransui, Sencha Hayashinan (煎茶早指南), 1802.

Chapter 6. Sōen and the Forest Needle

Nagatani Sōen (1681–1778) was a tea farmer from Yuyadani in Ujitawara, south of Uji. After about fifteen years of experiments, in 1738, he pioneered Aosei Sencha Seihō, literally, “blue-green sencha processing” [1].

Instead of pan-firing or coarse decoctions, he:

- Steamed fresh spring leaves immediately after harvest;

- Rolled and kneaded them on a hoiro table;

- Shaped them into fine needle strands;

- Dried them to completion on the hoiro.

This “Uji method” became the emerald standard for sencha and later gyokuro processing [2].

In 1742 the Ōbaku monk-poet Baisaō visited Sōen in Ujitawara, their encounter was truly an ichigo-ichie moment.

“Master Nagatani Sōen kept me in a room and brewed new tea from his own garden. At the first taste I found it the utmost in pure fragrance and elegance, surpassing anything under heaven”.

Local tradition holds that before leaving, Baisaō inscribed four characters on a wooden tray kept by the Nagatani family [3]:

「煎茶・日日・起・松風」

Sencha · Every Day · Awaken· Pine Wind

Sōen’s technique gave Baisaō a sublime leaf to brew; the Wandering Baisaō gave Sōen’s leaf a public stage. In 1954, the community enshrined him as the Tea Ancestor (Chasō Myōjin, 茶宗明神) at the Daijingū shrine next to his birthplace [4].

References