Tea is one of the cornerstones of Japanese culture (and history). Perhaps the most well-known of these are the Japanese green teas: sencha (煎茶) and matcha (抹茶). Matcha especially has seen a global meteoric rise in fame in recent years as matcha lattes, smoothies, and various sweet treats. Did you know that Japan produces other types of teas as well? Personally as an intern at Obubu, I have been pleasantly surprised to learn about the other types of tea produced in Japan. In this blog post, I would like to shed light on teas produced in Japan aside from green tea, to go beyond green. In particular, I would like to highlight an up and coming category of tea (that is also one of my favourites) — Japanese black tea.

An obsession over one single plant — Camellia sinensis

Most of the teas we consume come from the same plant — Camellia sinensis. Green, oolong, black, white and fermented teas (like pu’er, awabancha, goishicha, etc.) are all produced from the very same plant. The key difference lies in how the tea leaves are processed. Here’s a brief illustration of the different processing procedures behind various tea types and the list of possible processes are by no means exhaustive. New tea processing methods are still being developed and old methods continue to be unearthed from history research.

Different processing workflows have been developed to produce various teas from Camellia sinensis. The workflows here are examples inspired from a pamphlet by a tea shop in Kyoto (7T+). Photo credit: Till Jungjohann (intern #175). Chart designed by: Ng Ren Hui, Amanda (intern #173).

The two waves that influenced Japanese black tea

The second largest tea type produced in Japan happens to be black tea. Japanese black tea is known by many names including kokusan koucha (国産紅茶), jikoucha (地紅茶), and more recently wakoucha (和紅茶). I’ll be using the term wakoucha in this blog following the current preferred name.

Relative to Japanese green tea, wakoucha is the new kid on the block. While evidence for Japanese green tea can be traced as far back as the Nara period (710-794 AD), wakoucha appeared much later in 1875 (the eighth year of the Meiji period).

During the Meiji and Taishou periods (collectively spanning from 1868 to 1926), Japan saw several developments in terms of international trade. A slew of treaties was signed encouraging trade ties between Japan and Western markets (e.g. the United States, The Netherlands, Russia, Great Britain, France). There was a high demand for Japanese tea which spurred several important developments in the Japanese tea industry including the mechanisation of Japanese green tea production. Tea solidified itself as an important commercial good with exports spiking from 181 tonnes in 1861 to over 20,000 tonnes in 1903. In the midst of the excitement around tea export was Japan’s exploration into wakoucha.

Aside from efforts to improve Japanese green tea production (through mechanisation), the Japanese government observed the demand for black tea in these Western markets and decided to invest efforts into developing wakoucha. Two key waves of wakoucha development influenced wakoucha production.

In the first wave, Japan recruited the help of Chinese black tea specialists to teach and establish the production of Chinese-style black teas. The government published a document entitled the Black Tea Process Record (紅茶製法書) to spread the processing procedure of Chinese-style black teas. In 1875, the first wakoucha was produced.

In the second wave, a delegation led by Tada Motokichi (多田元吉) was sent to black tea-producing regions in China, India, and Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka). The delegation brought back seeds of the tea plant sub-species Camellia sinensis assamica. Notably, the assamica sup-species differs from the typical sub-species grown in Japan and China at the time namely Camellia sinensis sinensis. The assamica seeds brought back kickstarted the development of a tea plant variety that shared the flavour profile of assamica-based teas suited to Japan’s climate. Additionally, the techniques gathered from these regions were distilled into the Black Tea Manufacturing Training Regulation (紅茶製造伝習規制), a document focused on sharing the processing procedure of Indian-style black teas.

So why are these two waves important? These waves introduced different styles of black tea, which exhibit different flavour profiles. The term “black tea” tends to elicit the image of Assam or Darjeeling black teas, which are characteristically full-bodied teas that are darker, more tannic and more astringent. The flavour profile of these black teas pair well with milk, sugar and spices (think an Earl Grey or Masala Chai). These teas are reminiscent of the Indian-style black tea introduced by the second wave. In contrast, the first wave introduced Chinese-style black tea that tend to brew lighter (even appearing more reddish or gold) with more delicate floral notes that can be easily masked by the addition of milk and/or spices. Accordingly, these Chinese-style black teas are not typically consumed with milk or used in black tea blends with spices. Wakoucha is influenced by both these styles of tea, which have fed into the wide range of flavour profiles found in modern wakoucha.

The varied flavour profiles of modern Japanese black tea wakoucha

Wakoucha has seen a rather complicated and tumultuous history since its beginnings in the Meiji period, which is nicely discussed elsewhere (like in these articles with the Global Japanese Tea Association written by Sara Cherchi and Marjolein Raijmakers). Around the 1970s, wakoucha production came to a near stop and its renown domestically and internationally has been eclipsed by black teas from other regions (Darjeeling and Assam in India or Sri Lanka, for example). In the last two decades, however, wakoucha has seen what many have described as a “revival” (such as in this insightful article written by Cat Kerr for The Japan Times where George Guttridge-Smith, the Head of the International Department of Obubu also makes an appearance). Tea farmers are actively experimenting with the development of wakoucha, yielding a wide range of fascinating flavour profiles.

The playground for wakoucha development encompasses many factors. From selecting or developing a tea plant variety (also known as cultivar) to the cultivation location and cultivation method to the processing approach, all of these factors can be adjusted to achieve distinct flavour profiles. Here are five wakoucha I have had the pleasure of enjoying and learning about.

Obubu tea farm’s wakoucha

- Pine Needle Wakoucha

Akky-san (Akihiro Kita), one of the Co-founders and the President of Obubu, developed our Pine Needle Wakoucha.

PINE NEEDLE WAKOUCHA

Cultivar: Yabukita (やぶきた)

Cultivation method: Open field (露地)

Location: Tenku field, Wazuka-cho, Kyoto Prefecture

Harvest period: Summer 2023

Processing: Sun withering — Indoor withering — Oxidisation of leaves using the tumbling machine with light pressing — Rough-rolling — Separate leaves with drum machine — Shapping into needles — Drying using tea drying machine

Flavour: Light-body with little astringency, malty and vanilla rooibos notes

Akky-san sharing about pine needle wakoucha during a break while farming. Photo credits: Ng Ren Hui, Amanda (intern #173).

- Natural Black Gyokuro

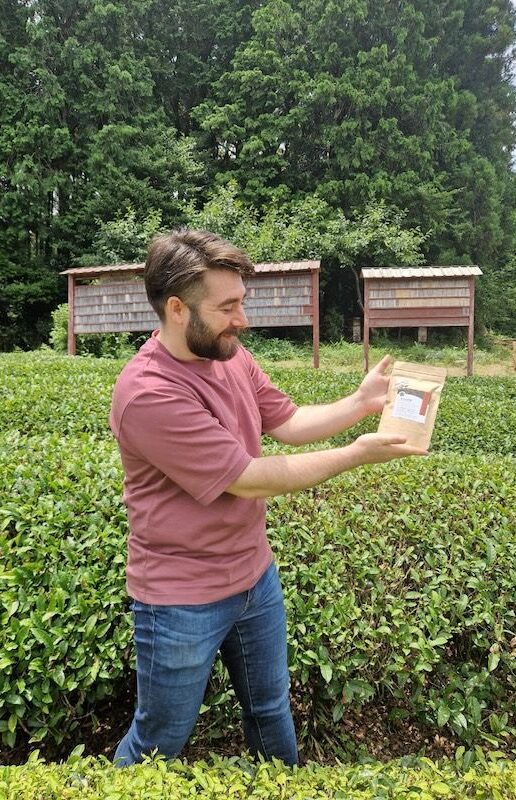

George Guttridge-Smith, the Head of the International Department of Obubu, developed our Black Gyokuro.

NATURAL BLACK GYOKURO

Cultivar: Yabukita (やぶきた)

Cultivation method: shelf-shading for 30 days (被覆)

Location: Aoimori field, Wazuka-cho, Kyoto

Harvest period: Spring 2023

Processing:Sun withering — Indoor withering/shuffling leaves by hand — Bruising the leaves by tumbling the leaves in a modified drum machine — Filtered out powder — Soft-rolling — Rough-rolling — Twist and curling — Separating the leaves with a drum machine — Shaping into needles (focusing on the panfried aroma) — Drying using shelf-style dryer

Flavour: Oily mouthfeel with medium astringency, slightly woody with dried cranberry and faint golden syrup notes

George sharing about natural black gyokuro. Photo credits: Ng Ren Hui, Amanda (intern #173).

- Limited edition wakoucha by Obubu interns and assistant managers

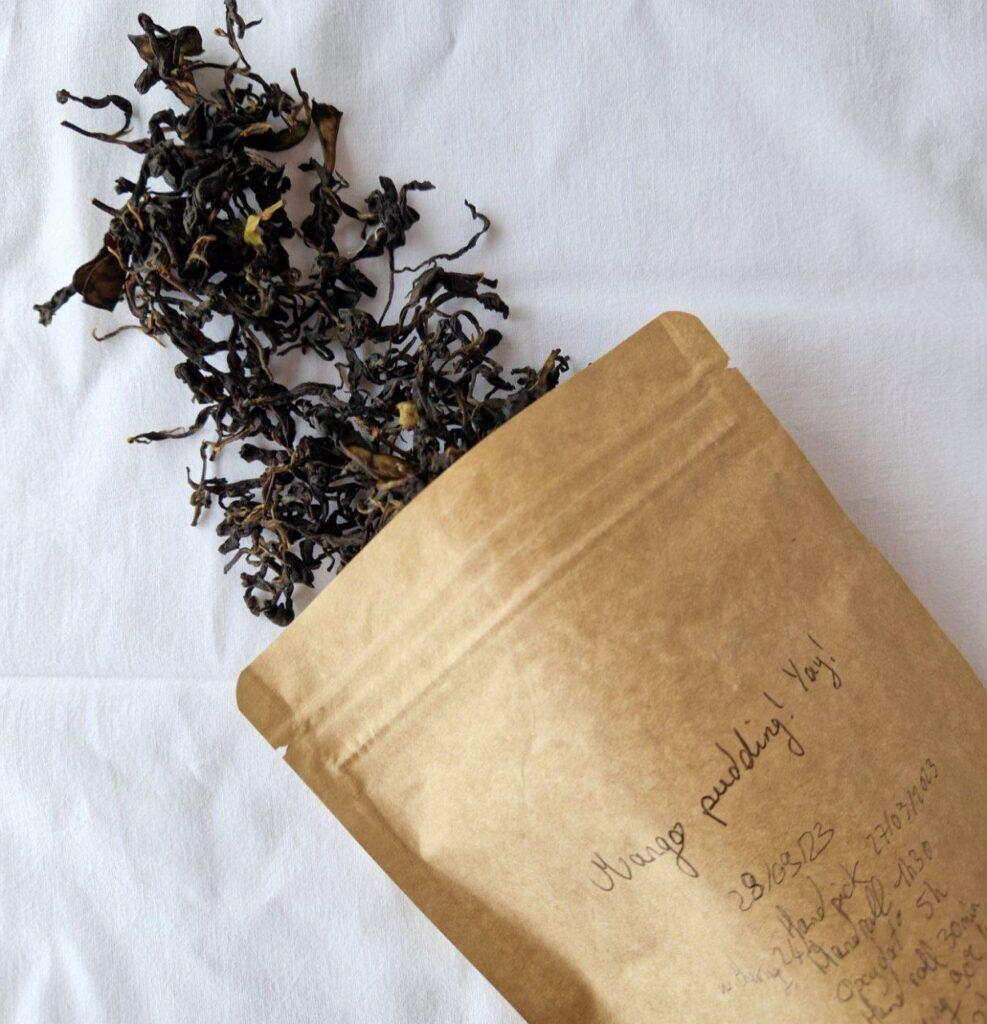

During the summer, interns at Obubu also get the opportunity to make our very own batches of wakoucha! (They are limited edition so please try them if you drop Obubu a visit.) I have yet to make my own so I will instead share about the wakoucha made by Jean Rosas, one of the previous Obubu Assistant Managers — Mango pudding.

MANGO PUDDING

Cultivar: Yabukita (やぶきた)

Cultivation method: Open field (露地)

Location: Aoimori field, Wazuka-cho, Kyoto

Harvest period: Autumn 2023

Processing: (handpicked leaves —) Withering — Hand rolling to bruise/oxidise and shape leaves — Hand rolling to shape leaves — Drying using a pan-frying approach twice and resting the leaves at room temperature between drying steps

Flavour: Smooth, medium-body mouthfeel with little astringency, honey notes and ripe jackfruit aftertaste

Mango pudding scattered over a white cloth showcasing the leaves. Photo credits: Ng Ren Hui, Amanda (intern #173).

Wakoucha from elsewhere

Aside from Obubu Tea Farms, other tea farms are also producing wakoucha. Here are two distinctive wakoucha I have gotten to try:

SAMURAI TEA FARM’S

ROASTED WAKOUCHA

Samurai Tea Farm uses a Taiwanese oolong processing machines for processing black teas. This particular black tea undergoes an additional roasting step.

Cultivar: Benifuuki (べにふうき)

Cultivation method: Open field (露地)

Location: Akinohara-cho, Shizuoka

Harvest period: Autumn 2023

Flavour: Medium-body with strong astringency, very bold (like someone bashing into a room screaming “Wakoucha is here!”) with coconut overtones and maple syrup undertones

MITOCHA TEA FARM’S

WAKOUCHA (大和紅茶)

Mito Tea Farms is known for preserving and incorporating folk techniques into tea processing. This particular tea is handpicked and is sun-dried at the end of processing (as opposed to using an oven or pan.

Cultivar: Okuyutaka (おくゆたか)

Cultivation method: Open field (露地)

Location: Kumano, Wakayama

Harvest period: Summer 2023

Flavour: Smooth and light-body with little astringency, Szechuan peppercorn notes

Morning tea session with Samurai Tea Farm’s roasted wakoucha at Obubu house. Photo credits: Ng Ren Hui, Amanda (intern #173).

Cooking with wakoucha

Aside from enjoying wakoucha as a tea directly, wakoucha has been explored as an ingredient incorporated into drinks and food. The Japanese chocolate brand Bourbon (ボルボン), for example, has mini chocolate-covered cookies incorporating wakoucha. There have also been some delicious creations made at Obubu like this refreshing iced shiso wakoucha and this delectable wakoucha crème brûlée (with many more you can find in this cookbook). I have also tried my hand at incorporating wakoucha into food recipes like this min chiang kueh (a pancake dish common in my home country Singapore).

Final words: wakoucha and beyond

The world of Japanese tea is wide with active experimentation by tea researchers, tea farmers, and the rest of the tea community. While green tea is perhaps the oldest tea type in Japan, there are other types of tea have arisen in history. In this blog post, I share about wakoucha, the two waves that influenced wakoucha development in Japan and the myriad of flavour profiles of modern day wakoucha. Just as how green tea has found its way into food and drink recipes (especially by way of matcha), wakoucha can also be incorporated into food and drinks.

This myriad of unique flavours arises from playing around with various factors like the cultivar used, cultivation method and processing approach. Notably, these same factors can be adjusted for other teas as well. Efforts throughout the long history of tea till now have achieved an incredible range of flavours not just for wakoucha and I hope this blog post encourages you to explore teas and the craft behind them for your next tea break.

Cheers,

Amanda

About the author and acknowledgments

Hi, my name is Amanda. I interned at Obubu from mid-April to mid-July 2024 and you can read more about me in my previous intern page. During my internship, I was surprised to learn about other types of teas produced in Japan aside from green tea. I also learnt about the multitude of factors which influence the eventual cup of tea. I wanted to share some of this fascination through this blog post. While writing this blog post, I received the help of many people at Obubu. To name a few: Pau Valverde Molina, an Assistant Managers at Obubu, shared the two black teas (and more that I could not fit into this blog post) from other tea farms. Akky-san (Akihiro Kita, the President of Obubu), Hiro-san (Hirokazu Matsumoto, the Event and Factory Lead of Obubu) and George Guttridge-Smith (the Head of the International Department of Obubu) shared the stories behind how the black teas at Obubu are processed. George also gave valuable feedback on the initial draft of this post and Sarah Mazza, an Assistant Manager at Obubu, shared with me about the exciting and contested history about the beginnings of tea cultivation in Japan.

References

Disclaimer on the history of wakoucha presented here

During the course of writing this post, I realised the immense breadth and complicated history of wakoucha. One of the challenges I faced was a lack of references to primary literature from articles about wakoucha history. Regrettably, I was unable to follow up on all the relevant primary literature within the time constraints of writing up this post in the Obubu internship. Instead, I referred to multiple articles written by others in the tea industry. I distilled consistencies in the narratives presented of wakoucha‘s history by these articles into the narrative presented in this post.

- Previous Obubu blog post about wakoucha

https://obubutea.com/japanese-black-tea/ - Awabancha processing workflow (used as an example processing workflow for fermented teas)

https://gjtea.org/awabancha/ - *Evidence for tea cultivation (and likely production) in Japan tracing back to the Nara period

A Bowl for a Coin: A Commodity History of Japanese Tea by William Wayne Ferris - Treaties signed encouraging trade ties between Japan and Western economies

https://www.itoen-global.com/allabout_greentea/history_of_tea/ - Statistics on tea exports from Japan between 1859 and 1965

https://www.nihon-cha.or.jp/export/english/trends.html - Development of black tea production in Japan from the early Meiji period

https://www.tezumi.com/blogs/tezumi-insights/japanese-black-tea-history-and-revival

https://www.soumu.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/01soumu/archives/0703kaidoku_05_2.htm

https://gjtea.org/japanese-black-tea-wakoucha/

https://gjtea.org/the-history-of-japanese-black-tea-wakoucha-part-2/