Hello! This is Cara, intern #189. My background is in food science with an interest in sustainability! In my eyes, sustainability is a practice of being mindful of our consumption of resources. As the saying goes, reduce, reuse, recycle! In this post we’ll be exploring the world of dyeing! That is, dyeing with upcycled tea.

The use of botanical or natural dyes can be dated thousands of years. Archeological evidence of wool dyed with madder and woad was found in Israel’s Timna Valley and dated to the late 10th century BCE. In today’s modern times, we have the option to use either natural or synthetic dyes. We have chemist Henry Perkin to credit for the commercialization of synthetic dyes. In 1856, Perkin was in his home lab trying to synthesize quinine, a medication used to treat malaria, but instead accidentally created a purple dye now called mauveine.

Why not be like Perkin and create our own dyes at home too? No chemistry degree needed.

All we need is food scraps! And a few other household tools.

Fruit and vegetable scraps are an excellent choice for creating natural dyes because they’re rich in polyphenols, which create their vibrant colors and stain clothes. Besides food scraps, natural dyes can be made from foraged flowers, roots, and spices. Table 1 displays a list of colors and the plants that can be used to create the respective color.

Table 1

| Color | Plant |

|---|---|

| Red/Orange | Beet Root Yellow Onion Skins |

| Yellow | Turmeric Chamomile |

| Pink/Purple | Butterfly Pea Avocado Skins |

| Green | Anise Hyssop Plantain Leaf |

| Blue | Black Beans Purple Cabbage |

| Brown | Tea Black Walnut Hulls |

Fabrics best suited for natural dyes are natural fabrics, such as cotton and linen (plant based) or wool and silk (animal based). Natural fibers have a chemical affinity toward natural dyes’ amino acid and protein structure and a porous structure that allows for enhanced penetration and retention. Additional substances can be used to improve the fabric’s color retention. These substances can be categorized as: mordants, binders, and pH modifiers. Mordants have two defining traits: (1) being a metal salt and (2) it creates an insoluble bond between dye and fiber. Examples of mordants include aluminum salts and iron salts. Copper, tin, and chrome may also be used, but are not safe for humans nor the ecosystem. Binders form soluble connections between the fiber and dye and act as a “glue,” which can degrade over time. Examples of binders include soy milk and tannins. Tannins can be naturally found in some plants and would therefore not require the use of mordants. Lastly, pH modifiers are used to prepare the fiber for dyeing or change the pH of the dye bath. For example, the acidity of a vinegar:water bath can be used to open up the fibers in preparation for dyeing. pH modifiers will turn the dye bath more acidic or basic. Generally, acid modifiers will make dye tones more yellow. Whereas, alkaline modifiers will make dye tones more pink.

Lucky for us, tea is rich in tannins and does not require mordants or binders. Although, we used a vinegar bath to prepare the fabric.

History of Dyeing in Japan

Japan has a deep rooted history in the art of dyeing as it was used to make the beautiful and iconic kimonos that Japanese culture is known for. This Japanese method of dyeing is called shibori, and it dates back to the Edo period (1603-1868). This method manipulates the fabric through folds, ties, and stitches prior to applying the dye to create intricate patterns. The name shibori is derived from the Japanese word shiboru which means to wring, squeeze, or press. Shibori fabrics are traditionally dyed with indigo, but the term shibori simply refers to the physical processes applied to the fabric before dyeing, not the colour. The art of Japanese indigo dyeing is called aizome.

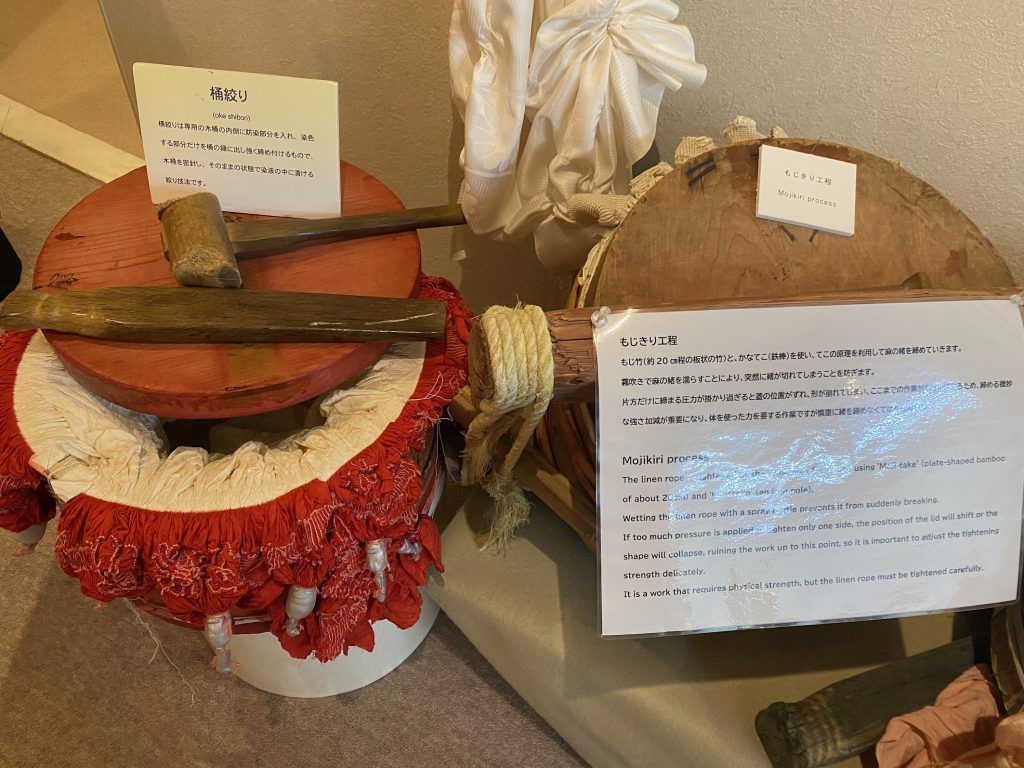

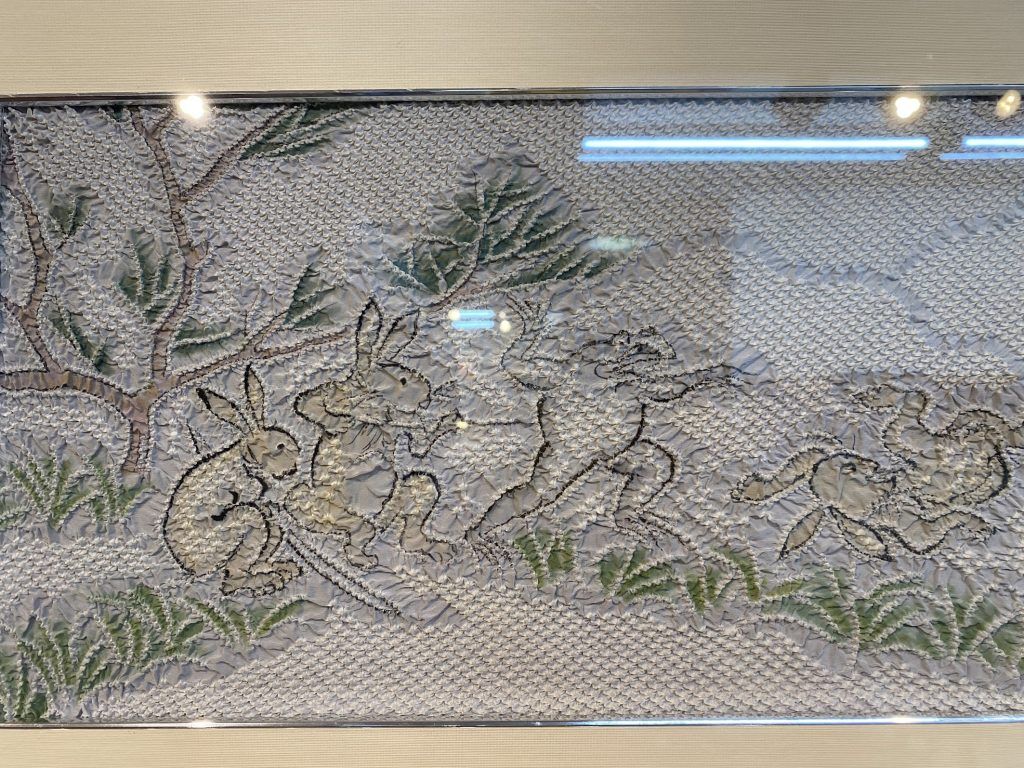

For project inspiration, Mia and I visited the Shibori Museum in Kyoto. It is operated by a family with generations of shibori artists with some of their personal works and heirlooms of traditional shibori tools in the exhibit. On display they have a large 3x2m seasonal shibori centerpiece (Figure 2). Each mural took 4 years to make! Since we visited in Spring, the mural featured a moonlit sakura tree with a bonfire. Other pieces in the exhibit included recycled shibori thread art, which used the leftover shibori thread to create a mosaic, and shibori art representing each of the 53 stations of the Tokaido Trail from Edo to Kyoto (Figures 3, 4, 5). The attention to detail of each shibori piece was truly so impressive. Please consider visiting the Shibori Museum during your next trip to Kyoto!!

While traditional shibori techniques require many years of practice, there are simple shibori patterns that can be done at home. Below are the patterns I used from some pieces.

Itajime pattern is an accordion fold vertically and then horizontally and tied together.

Kanoko pattern is a lateral scrunching of the fabric and tied together.

Wood blocks can also be used to compress the cloth and resist dye in the shape of the block.

Tea Dyeing!!

So let’s get into the tea-tails (details?). For my project I used two cloths: white rayon tea towels and t-shirts of unknown fabric, likely a cotton blend. The teas used were a blend of excess teas that weren’t of quality to sell in our shops. Please reference this as a guide, and feel free to experiment with tea types, dye bath water:tea ratios, and dyeing times!

Materials

Water

2L Stainless Steel Pot

Large Bowl

Wood Triangles/Circles

Rubber Bands or Thread

Scissors

Methods

Roughly 100g of tea was added to the 2Lpot and filled with water. The pot was placed on the stove at high heat and brought to a boil. Once boiling, the dye bath simmered for 1 hour. While the dye bath was simmering, I prepared a 2:1 water:vinegar bath and placed the cloth in the bath for 30 min. Then, I wrung out the cloth of excess liquid and applied a shibori pattern.

After the dye bath has simmered for 1 hour, I added the folded cloth into the dye bath and brought it back to a boil to simmer for another hour. After simmering, the dye bath-cloth mixture was left on the counter for at least 24 hours. The longer the exposure to the dye bath, the better! The dye bath and cloth were occasionally mixed to ensure even colouring.

After the 24-hour soak, the cloth was taken out of the bath and thoroughly rinsed in the sink until the water ran clear. The cloth was left out to dry completely and then machine-washed.

Ta-daaaa~ Results!

Below are pictures of how the samples and t-shirts turned out! It’s so exciting opening up the cloth after the dyeing process.

Shibori embraces the concept of wabi-sabi, which is the beauty of imperfection, transience, and simplicity. So a project may not turn out exactly as planned, and that’s okay! Remember to enjoy the process and appreciate your works of art.

Thank you for reading, and enjoy tea dyeing!

<3, Cara (intern #189)

References

Hatcher, Annamarie. “Exploring Natural Dyes: A Wealth of Color from Your Compost.” Spin Off, 2021, spinoffmagazine.com/exploring-natural-dyes-a-wealth-of-color-from-your- compost /. Accessed 3 June 2025.

Raumer, Andrea. “Natural Dyes in Fabrics: A Sustainable Choice.” Fabric Sight, 26 June 2024, www.fabricsight.com/blogs/posts/natural-dyes-in-fabrics-a-sustainable-choice.

“Shibori Dyeing.” Seamwork, sw-main, 2015, www.seamwork.com/fabric-guides/shibori-dyeing

?srsltid=AfmBOoqezEI-6wkAo1cXZZfuMGLnkqPFgxLbMyiRgZ63ziT8QYwlBnrI.

Accessed 3 June 2025.

Sukenik, Naama, et al. “Early Evidence (Late 2nd Millennium BCE) of Plant-Based Dyeing of Textiles from Timna, Israel.” PLOS ONE, vol. 12, no. 6, 28 June 2017, p. e0179014, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179014. Accessed 29 Nov. 2021.

Twitter, and Ohio University. “Guide to Natural Dyeing with Food Scraps.” Treehugger, www.treehugger.com/natural-dyes-food-scraps-5193947.

“William Henry Perkin.” Science History Institute, www.sciencehistory.org/education/scientific -biographies/ william-henry-perkin/.