Overlooking the Uji River, Asahiyaki is a pottery studio and gallery shop presently headed by its 16th successive generation of potters and has a rich history of 400 years. For the first time, the studio held an exhibition, ‘Asahi Yaki 423 Exhibition’ that featured works from all its 16 generations. Through the exhibition, one could sense how tradition in the lineage is revered. I observed how the style of the pieces evolved through the times while maintaining true to the Asahiyaki’s identity, which I got to learn later from Toshiyuki Matsubayashi-san. Toshiyuki Matsubayashi-san, who oversees Asahiyaki’s business operations, is the younger brother of Yusuke Matsubayashi-san, the present 16th Generation Kiln-Master.

What is your experience of being born into a family of ceramic craftsmen like?

The 400 long years of Asahiyaki’s history did not come easy. Many people tell us that being part of Asahiyaki’s history is important work and they encourage us to continue creating new history. A lot of hard work is involved to continue this work. Even though we have been fortunate, there have also been many hardships.

Asahiyaki has a specific character and people have an image of how Asahiyaki’s style looks like. We carry on the tradition and style of Asahiyaki from many years ago. We do not want to change the Asahiyaki’s way, and we can’t make a new style. We have seen how our grandfather and father make their ceramic wares, and those becomes our image of reference. The challenging part of our job which we are always thinking about, is how to keep the Asahiyaki likeness that will be well-liked by today’s generation.

Can you share with us what you do at work?

Unlike what you might think, my life was not all about Asahiyaki. After graduating from college, I worked in a company in Tokyo for several years. Some years ago, I decided to help with the family business. Asahiyaki ceramic can only be made by the oldest brother and its appointed artisans. So as the second brother, I organise and oversee the business-related matters, such as wholesales, exhibitions, and more.

Talking about your job, what is something you enjoy the most about your work?

To tell you the truth, until I came to Asahiyaki, I did not often brew teas with a kyusu (Teapot in Japanese) and chawan. It was unnatural for me to drink tea in this manner. During my first job in Tokyo, I hardly reached for tea. Now that I am back in Uji, I have been learning about tea from tea farmers and tea merchants who are from my generation. Through them, I continue to learn about Asahiyaki’s work.

I think that it is possible for anyone to enjoy tea and its appeal. I am passionate for everyone to enjoy tea, and I desire to convey its appeal to people. I feel confident in sharing my passion for both tea and Asahiyaki, and I find pleasure in explaining the details to people. It’s enjoyable when I can share my interest with people who are interested in Asahiyaki and I think the other staff members feel the same way. Recently, I have come to experience more joy when explaining to people who are initially uninterested.

I believe you have been involved in ceramics for a long time, has your way of thinking about ceramics changed?

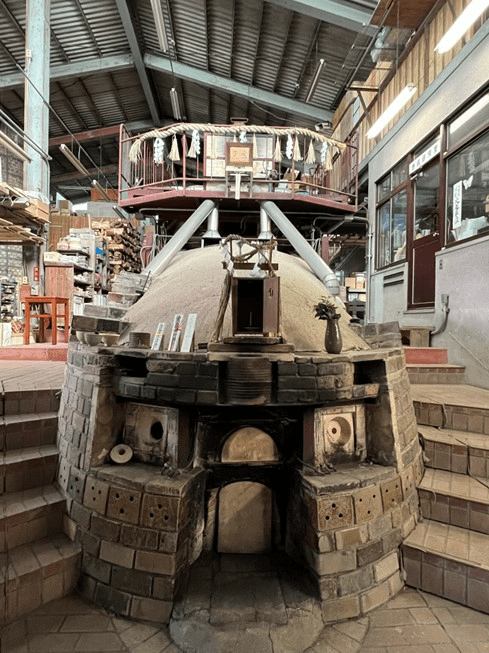

I used to think that pottery is a highly scientific and mathematical subject, as ceramic making seems methodological. The amount of glaze, the firing temperature in the kiln and the number of hours to fire is technical. However, as I got more involved with pottery, I have come to realise how pottery involves and forms harmony with nature. This concept intertwines with the Japanese idea of ‘Yaoyorozu no Kami’ (8 million gods, in other words, countless deities) which traces back to Shinto. The Japanese believe that everything has a god, even a grain of rice. In creating our chawan, the soil we use from nature, the wood we use from the trees to fire our pieces, the fire in the kiln – in all of these, we notice the presence of god in all of nature’s elements. I feel much closer to nature, and I see how nature is involved in our work. We respect and show gratitude to everything that is around us.

Pottery in Japan is rich in styles. Could you share how your work and studio are unique to the others?

It is difficult to explain what the style of Asahiyaki is. You could say that my elder brother was not explicitly taught how to create Asahiyaki wares, as learning the techniques does not mean one would nail down the look and feel of Asahiyaki. It is the duty of the successor to have observed the look and feel of Asahiyaki’s wares in their predecessors’ time. There is no precise or fixed timing for the handover of the generation kiln-master. The handover is dependent on each generation and when it will be taking place is not certain. For instance, my elder brother only assumed the responsibility as the 16th Generation Kiln-Master when he was confident that he understood the philosophy of Asahiyaki.

The philosophy of Asahiyaki has a close relationship to Uji (which is historically known as Japan’s centre for tea), we focus a lot on tea and making harmony with tea. We don’t want to just simply make teawares, we desire to contribute to the tea culture and tea history here in Uji. It is important for us to be close to the tea farmers, and to the teas.

Asahiyaki has a rich history of 400 years. How do you balance keeping the tradition of Asahiyaki and expressing yourself in your work?

I think our perspectives are a little different. Those who have started their own business might have a different perspective from us. As the tradition and work of Asahiyaki comes from many successive generations, the failure or success at a point in time is not that important. It is how we do what we do that counts. We always think in terms of how we can pass on our work to the next generation. It is not our work to express what we want to do because this work is not about an expression of our self. Therefore, we are not so conscious of expressing ourselves as we think that the accumulation of our work, that consists of all the generations’ ups and downs, is connected to the expression of ourselves.

When would you say are times that you have expressed yourself?

When I think of something that is atypical of Asahiyaki’s style, I consider it a big challenge to maintain Asahiyaki’s style while taking on this challenge. The frame of reference we use to judge our work is the tradition of Asahiyaki. I always work with an awareness of where the work I am doing now falls within that framework, and whether it is far from tradition or falls within it.

We make our products while being conscious of how we can come back to the Asahiyaki tradition even if we make big changes. Is it something that will change each time with the next generation? Is it something that will change while preserving Asahiyaki? Do you want to keep the traditional style as Asahiyaki’s style?

From my current point of view, I can see the traditional lineage of the past generations, but I don’t think that we are trying to create a path, but rather, it has been created through the challenges of the past generations.

We are not conscious of preserving the same traditions and styles but rather, we are building up new paths through challenges repeatedly. On the other hand, I think it is something that cannot be protected even if one tries to protect it. Tradition and things that have been built up over time.

My grandfather and father used to talk about the philosophy and approach to making things, and they used to say that there are two types of creations: randomness and workmanship. A craftsman can make 100 or 200 pieces of work, but as your hands become accustomed to it, you become able to make things without being conscious to some extent. When you finally have a beautiful line, the way of thinking about making things, for example, how to glaze, how to fire, and so on, are all connected to each other. If you make things consciously, you will not be able to make good Asahiyaki pieces. On the other hand, I don’t think tradition is something that can be protected even if one tries to protect it. Traditions and things that have been built up over time.

Like you have mentioned, tea ware and tea are so deeply connected. Asahiyaki also believes in “nare-kuru,” meaning that pottery is about 80% complete when fired, and the remaining 20% is completed when it is used more and more. Can you share more about this?

We are not just making artisanal wares, but we believe that we are making tea wares for people to enjoy tea for themselves and with others. Even if customers buy only one tea ware, I am happy if people find joy in enjoying tea with our tea wares.

An appreciation of loose-leaf tea drinking is declining in Japan, how do you think we could encourage people to enjoy tea drinking again?

These days, drinking PET (polyethylene terephthalate) bottled tea is one option to drink tea and it is the most convenient way to do so. It is easy to drink and easy to buy bottled teas and people are attracted to drinking tea because of it. Asahiyaki understands tea drinking with the tea wares like kyusu and chawan. It is then our mission to share with others how they can enjoy the tea drinking with tea wares too, and hopefully, more people will come to appreciate loose-leaf tea drinking. We try to get people to experiment with tea wares and encourage them to use tea wares, such as creating opportunities for them to use them. For instance, we rented a tearoom for a matcha brewing experience and shared information on tea and how to use tea wares.

What do you hope more people will know of Asahiyaki?

We try to share our philosophy and story to others, which could at times be difficult to share. But since that is what makes our pottery what it is, I think it is worth thinking of different ways to convey that. I value the communication we have with our visitors.

Thank you Miwako-san for translating, Sarah (Intern #146) for taking photographs and Sophie (Intern #147) for joining us on this tea adventure!

You can follow #145 Jia En’s adventures on her instagram page at @runawaybears.