As someone who picked up ceramics as a hobby over the last two years during the pandemic, I was enamoured by Japan’s long pottery history and the relationship between tea and pottery. I decided to interview the ceramic craftsmen who built some of the chawans (matcha bowls) that Obubu uses for tea tours and carries in-store.

Kuniki Kato-san is a 3rd generation potter that specialises in Kyo-yaki, which is a style of Japanese pottery that comes from Kyoto. Based in Toki city in Gifu prefecture, his family has been involved in the production of Japanese pottery since the Ansei Era (1854-1860). Today, Kato-san’s works take on a unique style as he merges Thailand’s Benjarong ceramic style of painting with bright colours and gold patterns while preserving the tradition of Kyo-yaki. I was able to learn more about his ceramics journey and experienced the art of chawan painting in his family’s studio whilst speaking to him.

How did your journey with ceramics start?

I am born and raised in a family of generational potters and painters, so for long as I can remember, I have been learning and practising pottery. I grew up watching how my grandfather and father made their ceramics. After graduating from university, I studied pottery making for two years and glazing for a year. After which, for two years, I practised making ceramic tableware at a studio. At another studio, I learned about chawans and tea wares for a year. I was 29 years old when I finally returned to my family’s studio, however, my works were still not considered good enough to be sold. It took more time before I sold my products. In the day, I would work at another pottery store and at night, I practised at my family’s studio.

Did you always know that you wanted to be part of the family business?

I was 10 years old when I knew that I wanted to continue my family’s business. I wondered why my family seal was not on our ceramic pieces. As it turns out, my family told me that because we are painters and not company builders, we can’t place our seal on them. So, I wanted to make sure that we could build wares of our own and paint on them.

What do you enjoy about your work? Is there something you enjoy making the most?

I like to listen to the customers and find out what they want so that I can make them happy with my work. I like chawan painting and mixing Thailand’s Benjarong painting designs with Japanese ceramic tableware goods.

What do you draw your inspiration from?

My inspiration comes from anything that I see and experience. It’s as though I have an antenna to see and be inspired by everything. What is currently trendy in the stores…The scenery of beautiful cherry blossoms…I connect what I experience to my art. In my travel trips to Thailand and Vietnam, I got a lot more inspired.

What keeps you motivated?

Developing new styles of pottery, such as integrating traditional and modern styles keeps me motivated. I learn and understand Japanese pottery and its tradition and studied Thailand’s Benjarong pottery. The patterns and techniques of Thai Benjarong are different from those of Kyo-yaki, but they are similar in their use of nature motifs in the designs and their emphasis on handmade, one-of-a-kind pieces. This made me think that a collaboration between Kyo-yaki and Thai Benjarong is possible.

The mixing of the Benjarong style of painting on Japanese ceramic ware is my way of expressing myself. I believe that Thai Benjarong is born in Thailand and has been created by many Thai craftsmen in their environment and culture. It’s important to cherish and protect the Thai tradition. I don’t want to just copy the Thai designs, so I engage artisans from Thailand to paint on my ceramic wares. I want to conserve the traditional Kyoto style, but I also want my ceramic wares to keep up with the trends.

Is it difficult to mix traditional with modern styles in Japanese pottery?

Colourful patterns are unique to Kyo-yaki (Kyoto pottery). Apart from that, Kyo-yaki does not have any specific rules. Kyo-yaki is about collecting techniques from different regions. Kyoto used to be the capital of Japan, it gathered and sold pottery from many different regions. This is different from the other regions that started pottery because they had ideal raw materials for it. So, that is why the origin of pottery in Kyoto has always been about mixing different techniques. In my factory, we use glass glazes but in some other places, they might be using another technique.

Teaware and tea are so deeply connected. As a ceramist, how has tea influenced your work?

Tea is indispensable to my work. I am a chawan maker. There is no chawan without tea and vice versa. Without tea, I would not have a job.

You have a studio in Thailand, is there a reason why you wanted to open a studio there? And how do you think the tea culture or tea ware appreciation differs in Japan and Thailand?

I wanted to expand my business overseas and have not made up my mind about any particular country. I was at the airport deciding on which country to visit and learn more about, and so I ended up choosing a flight to Bangkok, Thailand as the tickets were the most reasonably priced. On the aircraft, there was a guidebook on Thailand and there I saw images of Thai ceramics. I asked around and learned that I had to visit Chiang Mai, Thailand. That was how I started making many trips to Chiang Mai to learn about Benjarong.

The workshops I hold in Thailand are usually frequent by the upper class in the country. In my limited time communicating with customers from Thailand and Japan, I find that those from Thailand seem to know a lot about Japanese culture, teas and even flowers.

How do you think the Japanese pottery industry is evolving? If any?

The products themselves have not changed much, but the way of selling them has gradually changed. More effort is now put into showing how the teawares can be used. Instead of just exhibiting them on shelves, the teawares are used during tea-tasting workshops. When I explain the meanings behind the teawares, such as how chawans usually reflect the four seasons, I think it helps me to sell them better.

What dreams do you have for the future?

I hope to one day have students from different countries that I’m making pottery in, like Thailand, Vietnam, and Japan.

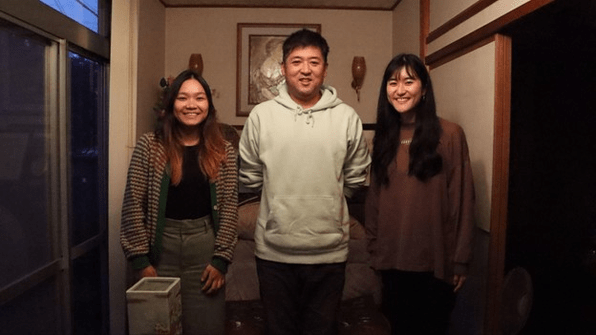

Thank you Saya-chan (Intern #132) for translating, Sarah (Intern #146) for taking photographs and Jean (Intern #107 and now Assistant Manager) for notetaking and of course, all three of you for being great companions! I can’t wait to see how our chawans will turn out :-)

You can follow #145 Jia En’s adventures on her instagram page at @runawaybears.