My name is Maren, intern #156, from Germany by way of the US and the UK. My academic background is in linguistics, and I’ve always been very interested in why we use the words we use, and how we manipulate language to create new meanings. In context of tea, which has such a complex global history spanning thousands of years, including contact, conflict, and exchange between numerous cultures and languages, there’s a lot that’s of interest to me.

So in my time at Obubu, I wanted to explore some of the language around tea in both English and Japanese. What do words like matcha and sencha actually mean? Where did they come from? Why are some terms translated into English in the international tea market, and others kept in Japanese? Where do Obubu’s tea names come from?

To answer some of these questions, I’ve created a short guide for incoming interns or any other curious folks about some of the most common terms used in tea in both English and Japanese, as well as some details about Obubu’s tea naming practices. In this blog post, I’ll share a few of the highlights of the project…

Tea and cha

Tea originated in China, and the character 茶 has been used since mid-Tang dynasty when it originated as a modification of 荼 tu, meaning ‘bitter vegetable,’ which referred to a variety of plants. At this point it began to be used specifically to refer to tea as a drink; at the time this took the form of pressed tea cakes ground into powder and boiled.

Tracing the exact history and etymology of this character is beyond the scope of this project, but various sources break it down in different ways – for example, as a combination of the radicals grass 艹, people 人, and tree 木. Other sources also indicate a relationship to the radical roof 宀.

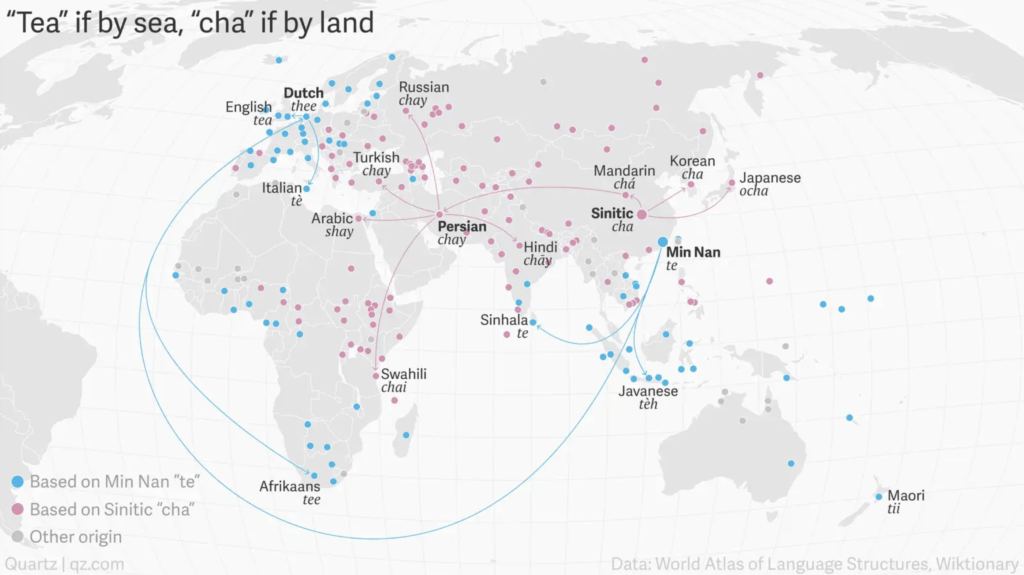

There a number of distinct dialects of Chinese, many of which have slightly different pronunciations of the character 茶. There are two which have made their way into most other world languages in some form or another – in the coastal regions of what’s now Fujian it’s te, while more inland it’s cha.

As tea traveled from China to other parts of the world, its name came with it based on the trade routes it traveled by. So generally, tea and words like it indicate sea-based trade routes starting in modern Fujian (initially via Dutch and Portuguese traders, then English), while cha and related words indicate trade routes over land (like the Silk Road). The land-based trade routes date back at least 2,000 years, while the sea-based trade routes began in the 17th century.

Funnily enough, the Japanese お茶 comes from the pronunciation that’s usually transmitted via the land route, even though tea necessarily came to Japan over sea. This is because tea came to Japan via Buddhist monks from central China, rather than through the coastal ports in Fujian using the te pronunciation.

In the Kyoto dialect, tea is also referred to as bubu, hence Obubu’s name.

Obubu’s teas

At Obubu, we use standard Japanese tea names for most of our teas, with some additions to differentiate our products. For example, we produce a number of different senchas, so we need to distinguish between these. Our main sencha productions are named for their season and cultivation method (Sencha of the Spring Sun and Sencha of the Summer Sun).

For more recent additions to our product catalogue, each name aims to evoke a connection to the natural world while conveying something of the tea itself, whether that’s flavour profile, liquor colour, aroma, or a reference to the cultivar the tea is produced from. This is particularly the case when we want to highlight teas we produce from cultivars we use less – for example, Sencha of the Gushing Brook is produced from the Saemidori cultivar, and the name references the clear green liquor colour this cultivar is famous for.

We also differentiate our matcha products by naming them after their cultivars, and we reserve the term ‘ceremonial’ for spring matcha. Other grades are distinguished by shading and season.

Our kukichas are all named after birds, again referencing the natural world and evoking a similar effect as the term karigane. These bird names are inspired by the look of kukicha, tea which comprises stem and twig material, resembling a bird’s nest. Suzume, roasted summer kukicha, is named for the sparrow whose nest most directly resembles this tea’s roasted twig material. Tsugumi, roasted summer kukicha made from shaded material, is named for the dark brown colouring the leaf shares with the thrush. Mejiro, our shaded spring kukicha, is named for the warbling white-eye, whose vibrant green plumage matches the tea liquor. Finally, tsubame, our shaded summer kukicha, is named after the barn swallow, whose arrival coincides with the harvest season of the material this kukicha is made from.

Using Japanese tea names like sencha, genmaicha, kukicha, and such in the international market, rather than translating these names, serves a few purposes for us. It’s a way to highlight Obubu’s authentic identity as a tea farm first and foremost, with deep connections to Japan’s tea culture and history. It’s also an opportunity to practice our value of education with customers across the world – even when tea names might be unfamiliar to customers, our product pages, blog posts, social media, and other content provide a wealth of information about the meanings of the terms we use.

Some of our tea names, like Sencha of the Autumn Moon and Hachiju Hachiya Sencha, also refer to important times of year or festivals in Japan. Given that Obubu’s values include community and education, these tea names aim to reinforce the connection between festivals, changing seasons, and tea culture.

We don’t use the label ‘organic’ for any of our teas, though we do have a ‘natural’ tea line. Organic certification requires a high cost (in money, time, and paperwork) that’s not feasible for a small organisation like Obubu, and not all organic certifications are recognised worldwide. So we’ve opted to forgo this certification, and instead produce a ‘natural’ line of teas instead.

These are grown and harvested without the addition of pesticides or fertilisers; the only thing we add to our natural tea fields are tea trimmings and leftover tea dust from our sencha productions. With this approach, we’re hoping to pioneer a more sustainable approach to natural farming, both in terms of environmental impact as well as feasibility for small organisations.

Thanks & the full project

I hope you’ve enjoyed this short excerpt of the project – you can download and read the full thing below if you’re interested in learning more! Other topics I cover are the distinctions between the terms varietal and cultivar, and oxidation and fermentation, as well as a list of common Japanese tea names like sencha and matcha broken down into their root meanings.

The greatest challenge of this project was keeping it within reasonable scope – with my academic background, it was tempting to try to turn this into an entirely too long and involved academic paper. Many thanks to Assistant Manager Jean for his help in restraining the scope of the project every time it threatened to get out of hand, and to the general vibe of Obubu for helping me foster this spirit of flexibility, creativity, and adaptation.

Thanks so much to all Obubu staff for many helpful conversations around this project and tea words in general, and special thanks to George and Kayo-san for their in-depth help and answers to my more specific questions. Thanks also to Obubu’s vast library of materials to draw from for the project, including previous interns’ projects, tea tour materials, blog posts on the website, and more.