Over the last several posts we’ve tested four of Obubu’s teas from all over Japan and all over the world. At least as much as one can do with eight waters, but it does illustrate an important fact. Depending on the water used to brew tea, the flavour of the tea can be drastically changed. If that’s the case, there is one important water that we have not used yet.

The Water

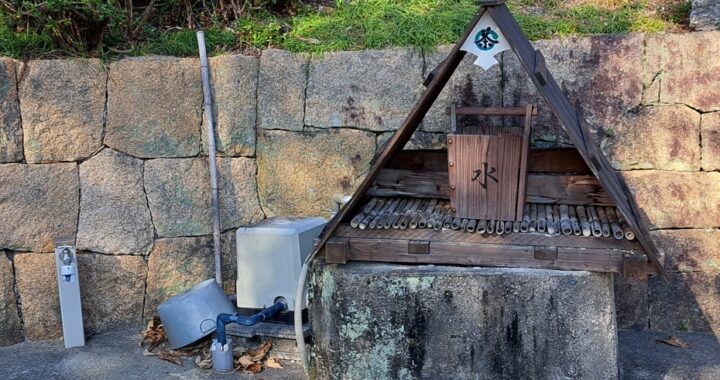

That is the water used by Obubu to test the teas that we produce. Specifically, we use well water right next to the office for brewing the teas at Obubu, and this is the water that is used to describe the flavors to the world. So today, we will look at the Obubu’s well water and how the teas brew with what we’ll call “Prime” water.

Something that unfortunately we will not be able to do is to look at the mineral content. There are no water quality reports for the Prime water, as far as I know, so we cannot look at how much calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium are in it.

Sencha of the Earth

No, I did not make this tea twice because the first time created such a different taste that I stared at the tea for a good minute trying to figure out what could have happened but then I realized that I put in half the amount of tea leaf that I normal did, thus bringing about such a sigh of relief that everything wasn’t suddenly a lie. No, that definitely didn’t happen.

There was a strong but light presence of umami. The umami was definitely present and noticeable, but gentle. It was bright with a pleasant bitterness lifting the umami up, keeping it from crashing. On top of all of that was a green vegetal flavour surrounded by really nice floral aromatics. There was also surprisingly a very light almost licorice spiced gum drop note, which is weird, but in a good way. When I accidentally brewed it with less leaves, the licorice spiced gum drop note was the dominate flavour which clued me that something was amiss.

It’s a shame that with us only testing one water this time around that we don’t have anything to compare with…

Unless…

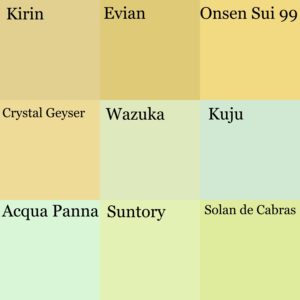

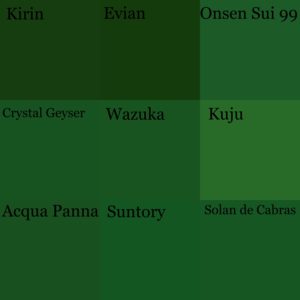

Below we have a color chart of Sencha of the Earth for every water that we’ve tested over these last weeks.

I think that we can have some easy takeaways from these visuals displaying all the tea/water combinations. And that is…with valiant attempts to keep lightning consistent, I clearly have some work to do. Also, if your phone catches on fire and then you drop it in water requiring you to get a new phone, the cameras take different quality photos. However, even with the camera issues, the affect of calcium on the water can be seen, the higher calcium waters are all more yellow (Evian, Solan de Cabras).

Amber Hojicha

I’m tempted when I continue doing these experiments into eternity to start off with multiple choice sections. With the Wazuka well water, amber hojicha develops sweet roasted notes, flavours that are reminiscent of spice, such as cinnamon, but not. There roast notes also leaned towards antique wooden furniture but there was some fruitiness as well. Fruitiness is not something too common with the hojicha, an interesting development to say the least. The fruitiness mixes with the spice notes to give a taste of raisins soaked in spice.

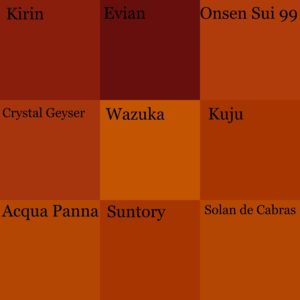

We have noticed in the past that Houjicha seems to buck the trend of the darker, more yellow, tea when the water has more calcium. I’m not entirely certain that isn’t what we’re seeing. Even though Kuju and Suntory are darker than Acqua Panna and Solan de Cabras (the higher calcium waters), I would argue that the higher calcium waters are more yellow. However, that wouldn’t explain the lower calcium waters being darker (and these photos were taken in the same conditions). None of the studies that I’ve found though studied hojicha, so there could be entirely different mechanisms going on.

Pine Needle Wakoucha

I hypothesized that perhaps teas could have several different flavour nodes based on the water, specifically because of previous tests with Pine Needle Wakoucha. In the case of Wazuka Prime Water

, the flavour dances between the two. There are the bright pecan shell notes, crisp, with no bitterness, but in addition there are some of those squash notes. In the case of Wazuka Prime Water though, the squash is much more of the zucchini variety, not the acorn squash. On the backend there is the very nice astringency that makes you salivate.

While there are differences across the different waters with the wakoucha, I wouldn’t say the differences are as noticeable as they are with sencha, especially when looking at the teas with the most consistent lightning conditions, with Suntory and Wazuka being the most similar. Suntory, as I mentioned before, was the water I noticed most at the tea festivals used by producers. That might mean something!

Gokou Matcha

Funny story. I chose this tea to test because I’ve had several gokou senchas previously that I loved. I never actually tried Gokou Matcha before, and I never tried it with Wazuka well water before starting this experiment. So this time was the very first time I tried the Gokou Matcha with Wazuka well water. I found the peach flavour! Well, there was a strong fruitiness that I would definitely not disagree with someone if they said it tasted like peach. The matcha was incredibly smooth with no bitterness or astringency with sweet green vegetalness as well. Out of all of the waters I’ve tried during these experiments, the Wazuka well water is the only one that has brought out the strong fruit notes, so I’m assuming it’s magical.

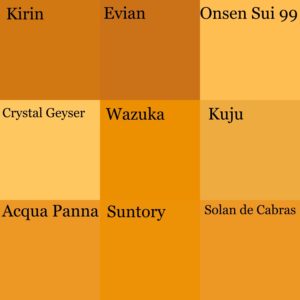

At the very beginning I thought that matcha would be the tea that water wouldn’t make too big of difference in the coloration. And while, yes, there may have been some…mistakes with the photos, the Gokou Matcha colors are all very similar, Kuju notwithstanding. In fact, Crystal Geyser, Wazuka Water, Suntory, and Solan de Cabras’s RGB values are all only a couple digits different. Why is this? We finally figuerd out the word I’ve been searching for this entire time. Pigment. Matcha would act as a pigment when mixed with water instead of an infusion. The science that we’d need to explore is the affect of water content on pigments. And guess what? I absolutely searched for that science. And guess what? I absolutely could not find anything on it, aside from one blog where they discussed it. (And then the comment section was full of artists talking about the importance of water. Dear Artists, please stop making art and start writing intensive scientific articles, please and thank you.)

So…Now what? The majority of you do not have access to the water from Kyoto Obubu’s well, and as we’ve seen over the last several of posts, it’s not as simple as finding another Japanese mineral water. If you visit Obubu for a tea tour, they’ll probably allow you to take some water but other than that? Is there anything that can be done?

No. So long! Farewell! It has been a blast researching these waters and writing these posts over the last few months, but it is time to bring it to a clo…

Water Wizardry

Several posts ago, we did some experiments with calcium chloride. I never fully explained why I even had calcium chloride on hand. The four minerals that we’ve kept track of have been calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium. Could…could…could we just…make our own waters? Absolutely.

A secret goal of these experiments has been to come out at the end and design a water that is a close facsimile to Wazuka’s well water, a water that anyone in the world could make, with the right materials, and be able to experience Obubu’s tea with something close to Obubu’s water.

Distilled or purified water with no added minerals is essential. It acts as a pallet for us to add our other minerals to. To the distilled water we can add forms of calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium, in this case we will be using calcium chloride, magnesium sulfate, sodium bicarbonate, and potassium bicarbonate. All of these are found in mineral water so we are not adding anything that water wouldn’t naturally have. Now that we have our building blocks, lets make some water!

But where we do start? We can’t just throw minerals into water and hope for the best, there has to be some method. Our first step is going be looking at water reports for Wazuka, Japan. These reports list the concentrations of a multitude of different chemicals and minerals in Wazuka’s water. However, that does not mean it will be the same for the well water. We are going work under the assumption that the reports are actually detailing the tap water, but it is still a place to start.

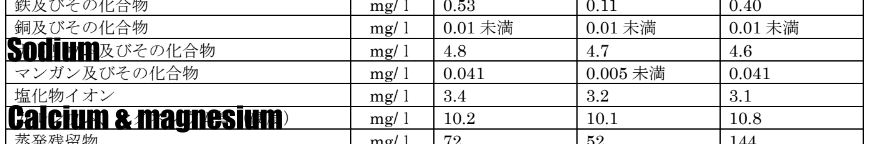

(Figure 451. Excerpt from the 2018 Wazuka Water Report showing the mineral content of sodium, magnesium, and calcium.)

According to the 2018 report, Wazuka water has 10.2 mg/L of calcium and magnesium (and etc…), 4.8 mg/L of sodium(and it’s compounds), and no listed potassium. The combination of calcium and magnesium into the same number will cause some issues recreating the water, but again, we are assuming this is the tap water, so it’ll at least be a start.

The First Trials

For this first trial we are simply going to take the calcium and magnesium value and just use calcium and see what happens. We’ll use the sodium value and no potassium, and from there we’ll keep going.

First off, the Wazuka well water brews up a little more yellow than the manufactured water. From previous posts and experiments, what does that mean? We need more calcium. Perhaps additional magnesium will increase the yellow color as well. Most of the experiments have been done with calcium, so per…Should we do a quick experiment with magnesium?

The manufactured water has a light umami that quickly fades away. The Wazuka well water has a much longer lasting umami that fills the mouth. Almost a little too much with this tea (We’re using a different tea than the past blogs for these initial trials. Our internship comes to an end in several days, and I have some tea I need to get rid of. There is a little sharpness to the manufactured water as well. A sign that the balance may be off towards sodium? Perhaps. (Little did they know, they were wrong).

We have to add the magnesium and potassium. It’s as simple as that. At least that part of the decision. How much is the real question. Because there is the lacking umami, I think we might as well just try to adding the same amount of magesium as we had in calcium. That’ll increase the hardness without relying too heavily on the calcium. We can also see if there an increase in the yellow color as well. Because we don’t have much information on potassium, this trial is going to be guess work. Maybe, let’s just add in the magnesium and keep the sodium the same and no potassium. As we’ve seen before in Evian, potassium is not always listed. If there is one thing I despise, is changing multiple variables at the same time.

Now with the second attempt, the colors are pretty darn close. The addition of the magnesium has given the tea a bit more body. The umami is boosted a bit and the sharpness is a little more smooth. The bulk of the umami though appears closer to the end of the taste with the manufactured water while the Wazuka well water has a much more upfront umami with a little more length and an overall earthier flavour. The back end of both the waters feel pretty close. Very close in fact. The front end needs the work though. This leaves me with a question though. Does magnesium affect the umami more on the back end while calcium affects it on the front end? More importantly, do I have time to test that thought?

The Following Trials

It may have sounded like I was close with the second second and in some ways, I was, and in a lot of ways, I was not. What followed were several trials that sorta hit around the same area, but were just lackluster in comparison to the Wazuka well water. There was something missing. My primary focus on most of these first trials were calcium and magnesium, in part, because most of the research on the affects of minerals on the flavor of tea dealt with calcium and hardness. The turning point came when I decided to check the TDS. In reality, I should have been doing that with all the experiments. The TDS of Wazuka’s well water is 103, and these first trials, well they were hitting the 30s. This was a sign that I just wasn’t adding enough to the water. So I did. Most importantly, I increased the amount of sodium I was using.

Remember how earlier I thought the balance of sodium was off, creating a sharpness in flavour? Nope, I was wrong. When I started to increase the sodium in the manufactured water, the flavours started to become more bold and vibrant. And then, Trial 6, sodium was the prominent mineral in the manufactured water, as opposed to calcium.

These back and forth trials continued on for about another ten trials. Finally, and with the help of Rie from Tea Curious, we came up with an answer. Is it perfect? Unfortunately no. It wasn’t likely we’d be able to make it perfect, while we focus on calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium, there are many other minerals in the water. These are the most prominent, but a dozen other minor flavors add up. But is it close? It’s pretty darn close. Without further ado…

Prime Water Formula

The End

Whelp, my time at Kyoto Obubu Tea Farm has come to an end, and thus these trials have come to an end as well. Lastly, I would just like to say. There isn’t anything wrong with tap water. Bottled water, while fun to experiment with, really shouldn’t be the go to for brewing tea. Sure, some waters may make a more delicious tea, it is far more important to learn to enjoy tea regardless of the water.